Agriculture, Farm Operation January 01, 2022

Farmers are aging out quickly

But farm help exists, if you look in a new spot.

The stats. The average age of farmers has been going up. According to the Census of Agriculture, the average age in 2017 was 57.5, nearly 10 years older than the first reported average from 1945. To reach this new average means 34% of farmers in 2017 were 65 or older.

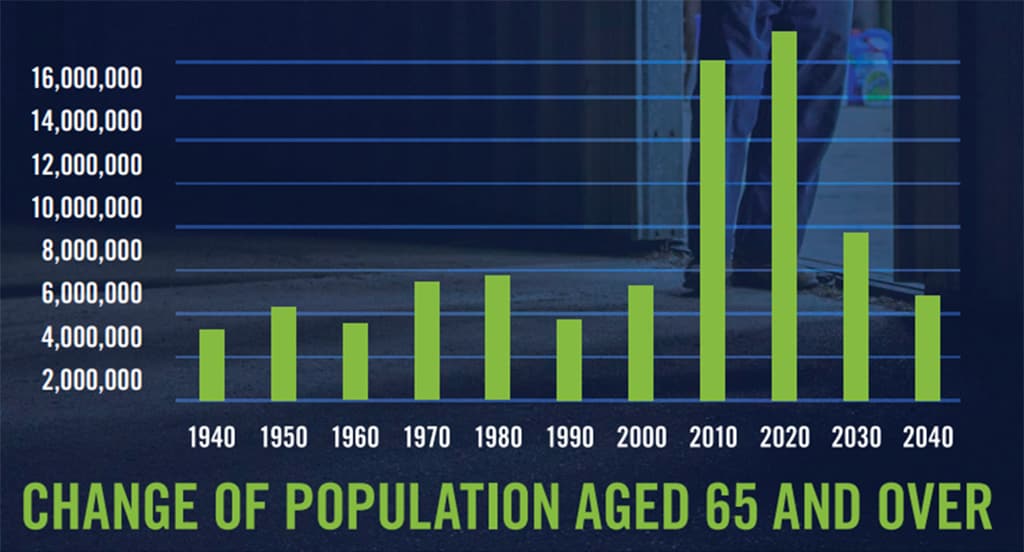

The graphic below shows how many American baby boomers entered the 65-years-old and older category last decade and will enter it in the next.

A similar data set was presented by Minnesota State Demographer Susan Brower to the Minnesota Ag and Rural Leadership Program last summer. She said, “I’m sharing these numbers with you because they will impact every community. This is something that’s going to have wide-ranging impacts for all residents.”

Above, left to right. A significant amount of farmers and farm workers across the country—including Don Weiland, of Garner, Iowa, and Brian Kelsey, of Granville, Ill.,—are also in the two, towering columns to the left with Knapp, creating a farm labor issue as they think about retiring.

By simply advancing her slide, all the air was sucked out of the room. Everyone gasped at the realization that—all of a sudden—a lot of people are 65 and older.

“The baby-boom generation is moving up above the 65-year-old age mark. And they are beginning to impact things like labor force growth, just by their absence in the workplace,” Susan explained. “With the baby boomers moving out of the workplace and the smaller Gen X, millennial, and Gen Z groups taking their place, there’s just not enough people to keep up the level of growth that we’ve had in the past.”

The question of why it is so hard to find anyone willing and able to help on the farm makes more sense with this data. They have aged out. Many hired hands are also baby boomers and seem to be actually retiring. To make matters worse, the younger generations are much smaller.

“Employers in the 1990s had no idea we had so many people. They could go to their newspaper and post a job or go to their headhunter and in would come all kinds of resumes from qualified applicants,” Susan remarks. “But as the baby boomers retire and the economy stays strong, we will have a really tight labor market for the foreseeable future.”

Some new options. There are qualified, reliable people out there who want to work part-time and full-time on farms. Finding them is the challenge, but the good news is there are at least three new ways to do so.

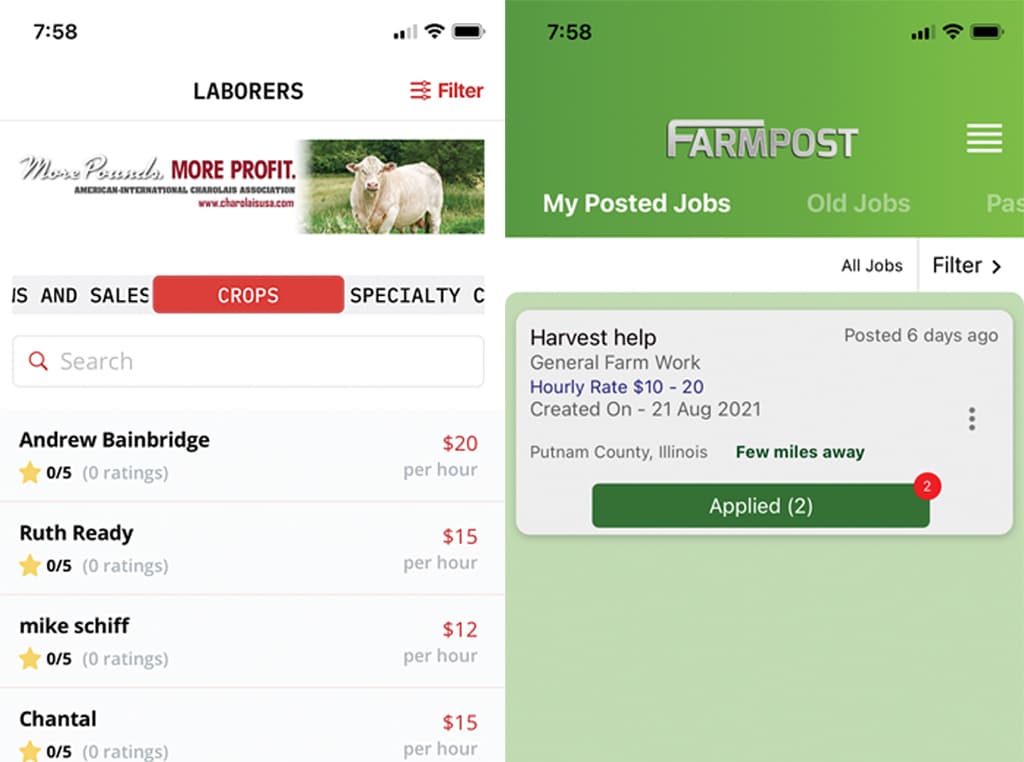

Above. Farmmee co-founder, Cindy Rockwell, demonstrates how to request help baling hay in their app. Inside the AgButler app, farmers can see a list of laborers available in their area and can rate them after completing the job. In the FarmPost app, farmers are notified as soon as people apply for their jobs.

“I don’t know how many people have told me they tried to use Indeed [a general job posting website], and it either gets lost in the shuffle or the candidates have zero experience,” says Kevin Johansen, founder of AgButler. After experiencing the same labor issue on his family’s Missouri farm, he built an app that serves as a farming gig-economy platform. Farmers post jobs they need done and match with vetted, nearby workers.

“We always say we know who is available or not in a 5- or 10-mile radius, but by expanding that to 30 or 40 miles through the app, farmers are finding the help they need,” Johansen says. “This is a very new way of sourcing labor. You might not always know the person, but you should know through the app [as opposed to a site like Indeed], it’s somebody with experience or the willingness to learn and do a good job.”

Three Iowa women are tackling a different part of the farm labor issue with their app, Farmmee, that allows people with equipment to offer their availability to other farmers.

“The easiest way to think about it is baling hay, planting, or harvesting. If one guy has equipment and is done early, he can help the neighbor, or a farmer needing extra equipment because of a breakdown can request help,” says Molly Woodruff, Farmmee co-founder. “This helps owners maximize their expensive equipment and fills a big labor gap.”

Another app that is designed more for steady part-time and full-time jobs is FarmPost. Of the three, it has been online the longest and therefore also has the most users—tens of thousands across all 50 states.

“We connect the farmer and the farmhand. The hiring process is then done individually offline, but we know 85% of our job postings see a minimum of three to five quality applicants. And most users on the farmhand side are aged 24 to 33,” says Michael Schaeffer, FarmPost founder.

All three apps reviewed have very generous customer service because they know it is a very different process than word-of-mouth or newspaper help-wanted ads. They truly want to help solve the farm labor issue because they all have farms, too. They want you to call with questions.

“I believe this is the future, as we’ve already proven the last couple of years of filling jobs for farmers, but there is a learning curve for finding employees through an app,” says Schaeffer, who is also an Iowa farmer. “I will personally do anything I can to help my customers adapt to using the platform.” ‡

Read More

AGRICULTURE/EDUCATION

Dryland Corn Dynamics

Careful management helps to reduce risk.

AGRICULTURE/EDUCATION

The Flat Car Fix

Retired railcars replace rural bridges for a fraction of the cost of a new structure.