Rural Living, Specialty/Niche December 01, 2022

Limestone Cowboy

.

An artisan continues limestone craftsmanship.

In the shadow of a modern wind turbine within a remote pasture on the Kansas Smoky Hills, Jon Pancost puts the finishing touches on a payload of nearly 100 century-old fenceposts made from native Kansas limestone.

Each eight-by-eight-by-72-inch post weighs roughly 250 pounds and despite the heft, are fragile after decades of exposure to the Kansas weather extremes.

Pancost adjusts bands securing the posts to a dozen pallets before loading them onto a semitrailer, after which the limestone payload is destined for Michigan where the stone will take on new life, presumably in a homeowner's landscape. Against a gray, cloudy sky the slight whir of the Smoky Hills Wind Farm turning in the breeze harmonizes with I-70 traffic in the background. The juxtaposition of old and new technology is not lost on Pancost, a limestone artisan from nearby Lucas, Kansas.

Limestone is his medium; almost all of it exclusively Greenhorn Limestone, the unique yellow limestone found only in a stretch from Washington County in north central Kansas, 250 miles southwest to Dodge City.

"The west was won with this stuff," notes Pancost wistfully.

After the Homestead Act of 1862, settlers were allowed 160 acres of public land provided they could improve the property, including installing barbed wire fence.

"There were no trees, nothing to build fenceposts with. Somebody came up with the bright idea of using limestone from these outcroppings. An entire economy was built out of it," he says. Now, however, limestone fenceposts are no longer practical and to many landowners are a nuisance. They are glad to rid their pastures of them.

Salvaging limestone fenceposts is a bittersweet component of Pancost's enigmatic profession. One day he and his crew are rebuilding the shell of a burned opera house in Wilson, Kansas; the next he puts the finishing touches on a monument to the founders of the little town of Denmark, Kansas. He has disassembled homes stone by stone, rebuilding them hundreds of miles away; he's worked on additions to buildings locally.

Greenhorn Limestone is unique in that it quarries easily and readily breaks into blocks that are easy to work with for quarriers and builders, says Greg Ludvigson, senior scientist emeritus at the Kansas Geological Survey.

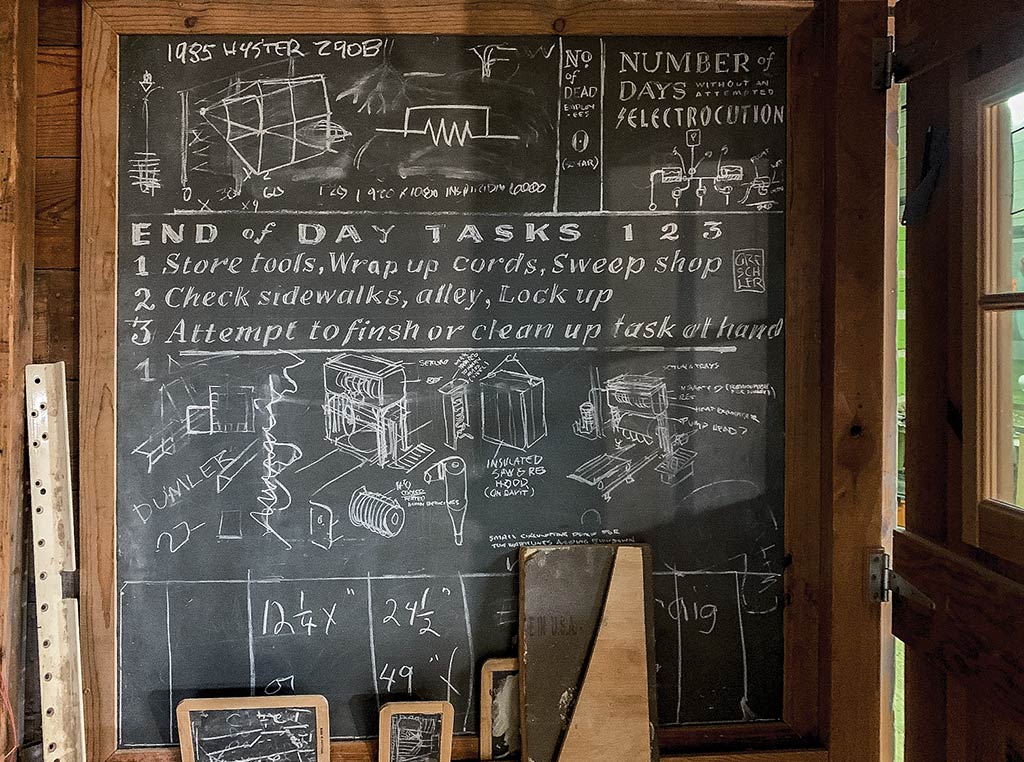

Above. On a chalkboard inside the old lumberyard in Lucas, Kansas, the day's tasks are artfully displayed. Fenceposts made from Greenhorn Limestone still dot the prairie landscape. A load of 112 limestone fenceposts is destined to a landscape project in Michigan from a pasture in the Kansas Smoky Hills. Pancost secures a pallet of fenceposts before loading on the tractor trailer.

Ludvigson, who has studied limestone throughout his career, reckons the Greenhorn Limestone was formed roughly 90 million years ago, during the Cretaceous age. Soft ocean sediment—microscopic in size—"oozed" to the sea floor and eventually fused into limestone after eons of pressure and weight.

"In many respects, it lends itself to dimension and breaks into pieces six-inches to a foot thick. Many carbonates don't have those characteristics," he says.

Stonemasons were able to quarry remarkably uniform sizes of soft limestone, which proved to be ideal building material for emigrants, many of whom were stonemasons or builders in other parts of the world. They were eager to ply their trade when building their new communities.

"If you aren't looking closely, it looks like brick. That's striking about it. It's not a mystery that it was used, because Greenhorn Limestone lends itself to that," Ludvigson says.

Like all limestones, however, the materials weather over time. Downtown Lincoln, Kansas, is proof. An array of architectural styles featuring Post Rock limestone line both sides of Court Street. Pancost points out the detail of quoins (corners) on one building; cornices on another. The town's commercial district was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2020, but many of the buildings show signs of fatigue, years of exposure to freeze-thaw cycles and acid rain taking their toll on the limestone. Pancost and his crew will soon tackle the restoration of an entrance to a former bank building in the community.

Above. After "green" rock was quarried, they often were faced, or trimmed with a mallet like this. To make fenceposts, settlers drilled holes in the soft, green stone, then inserted "feathers and wedges" which when tapped upon, pried the stone apart. Near Denmark in Lincoln County, Kansas.

Pancost never set out to be a stonemason in central Kansas. An Ohio native, he moved to Montana and eventually Utah. He moved there for the adventure—hiking, skiing, mountain climbing. Those hobbies didn't pay the bills, so he latched onto a stoneworking crew. Prior to a trip back from Utah to Ohio, he was told by a friend he should see the stonework in Kansas.

"I thought my friend was crazy. I mean, where do you get stone in Kansas?" he recalls. But he toured stone structures in Russell, Kansas, with a member of the local historical society. "And I went for a little drive in the country, and I'm looking at all these old stone buildings. I just couldn't believe people let them fall apart, because there is so much work that goes into them," he continues.

After tying up some loose ends, Pancost moved to Kansas in 2003. He had placed an ad in a weekly newspaper to see if anyone was interested in letting him salvage limestone buildings. Within a week, he had more than a dozen phone calls.

"On a Sunday, I pulled into a café in Lucas. Someone asked me what I was doing, and I told him I was looking at old stone buildings. He told me I needed to check out this bed and breakfast down the road that a young lady had restored," he says. "So I went, and there was an event going on, with all these people, and a beautiful woman walks by with this radiant smile. And I said, ‘I guess I'll stay here for a while.' And that's where I live to this day."

Nearly 20 years later, Jon and Becky have three teenage children and a unique business housed in an old lumberyard in downtown Lucas.

He's made a living of a painstaking, difficult, and rewarding vocation.

"It's a means to an end sometimes, but the end product being worth the amount of toil and trouble and pain sometimes that you go through to achieve it. I like to see things that last."

Equal parts artisan, philosopher and poet—Pancost's Facebook page, Bluestem Quarry and Stoneworks, is filled with thoughts on the lasting craftsmanship of stonework —Pancost believes he is rekindling a lost art.

"When I first came out here, it felt as if the Post Rock era was pretty much dead. There were no stonemasons left out here. It was one of the reasons I got into salvage when I first came here. I thought I'd just try to reclaim that which people have abandoned," he explains. "I've made an effort to pass this heritage along, even if it's just for another 15 or 20 years."

When it's difficult to make sense of forces outside Lincoln County, Pancost finds joy from this work. "It makes me feel connected to the past and hopeful for the future. Maybe we'll make something of ourselves here, even if it has to be carved out of a rock." ‡

Read More

AGRICULTURE, FARM OPERATION

The Other Side of the Coin

After you know your numbers...

AGRICULTURE, EDUCATION

Sankofa Farms

Cultivating ag skills and aspirations for Black youth.