Agriculture, Sustainability March 01, 2021

Palouse Prairie Protectors

Their native seeds help restore a dwindling resource.

Prairie is a rare find in the Palouse. Despite the pitching and rolling landscape, nearly every inch is seeded, producing some of the world’s finest wheat and legumes. Combines skirt ledges and drills bite into the edge of roadside gravel. Only the rockiest and steepest — anything over a 45-degree slope, though some push even that — aren’t farmed. There lie the prairie remnants.

While they may not produce premium soft white spring wheat or sport the odd looking short, plump heads of club wheat, the remnants are critical to supporting surrounding ecosystems.

“Diverse species in the prairie remnants provide continuous habitat for pollinators and valuable food and nesting areas for birds and other species,” says Jacie Jensen, who farms with her husband, Wayne, near Genesee, Idaho. Many are at risk of takeover by invasive weeds, such as ventenata grass — a cheatgrass-type species that could be devastating to crops, pastures and wild areas.

The Jensens are helping reinforce remnants and reintroduce diversity to CRP and pastureland by dedicating hundreds of their 5,000 crop acres to growing wildflower and native grass seed.

Prairie push. Though now passionate about caring for prairie remnants, it was pure economics that had wildflower seed production turning their head.

Wheat hit a paltry $3 per bushel in 2004. With the low came the realization it wouldn’t pay to plant some of their poorer fields. While mulling what to do instead, a random comment got the Jensens thinking about a new venture.

“They said our farm had one of the best Palouse Prairie remnants, one that had never been tilled,” Wayne says. A high ridge scattered with trees, rocks, grasses and flowers was mostly serving as a hiking area for those looking to take in the incredible panoramic views (see image above.) “At that time, people were starting to convert tougher fields to forbs and native grasses. We figured we could grow seed on our poorer ground for our own restorations and to sell to farmers and agencies doing restoration work.”

From scratch. Even today, seed is not readily available for most Palouse wildflower species. As a result, the Jensens hand collected their remnant and others.

“We could have purchased a few species, such as blanketflower, but they’re not wild. They’ve been selected to mature at one time,” Jacie says. “We keep our genetics as wild as possible as our seeds go to CRP reconstruction, prairie re-establishment or natural lands fire restoration work.”

Having plants mature at different times benefits insects and animals that use them and gives the plants a better chance of survival when facing pests, disease and other environmental challenges.

Seeds were planted in rows and increased until they could plant small fields then bigger fields.

Nearby University of Idaho, Washington State University and Pullman USDA ARS specialists were great resources.

“They helped us navigate species selection, propagation and pest challenges,” Wayne says.

Blanketflower, Western yarrow, penstemons, Lewis flax, arrowleaf balsam root and dozens more were tried over the years. Today, six wildflower species and eight or more native grasses are grown in fields. Plots host an additional 10 species, such as golden rod and native aster, for evaluation, seed building or special projects.

Their farm, Thorn Creek Native Seed, produces specialty seed specific to their region which is critical for reconstruction work. They also sell on a wider market.

This farming is not for everyone.

“It’s a slow process, taking three years to get a flower for most species. The first year they sleep, putting energy to the roots. The second year they creep and the third year they leap,” Jacie says.

They use profits to improve their land and plots serve as a lab of sorts as they seek to diversify rotations on commodity fields.

“Land improvements are done for our grandchildren. It’s like planting a tree, the benefits go to the next generation,” Jacie says.

Blanketflower at various levels of maturity. While making harvest more difficult, diverse genetics are ideal for conservation work. Prairie smoke in a production row. Beneficial hoverfly on goldenrod.

Oregon checkermallow drying. Most crops are swathed and dried in the field or barn before threshing.

Read More

Agriculture, Ag Tech

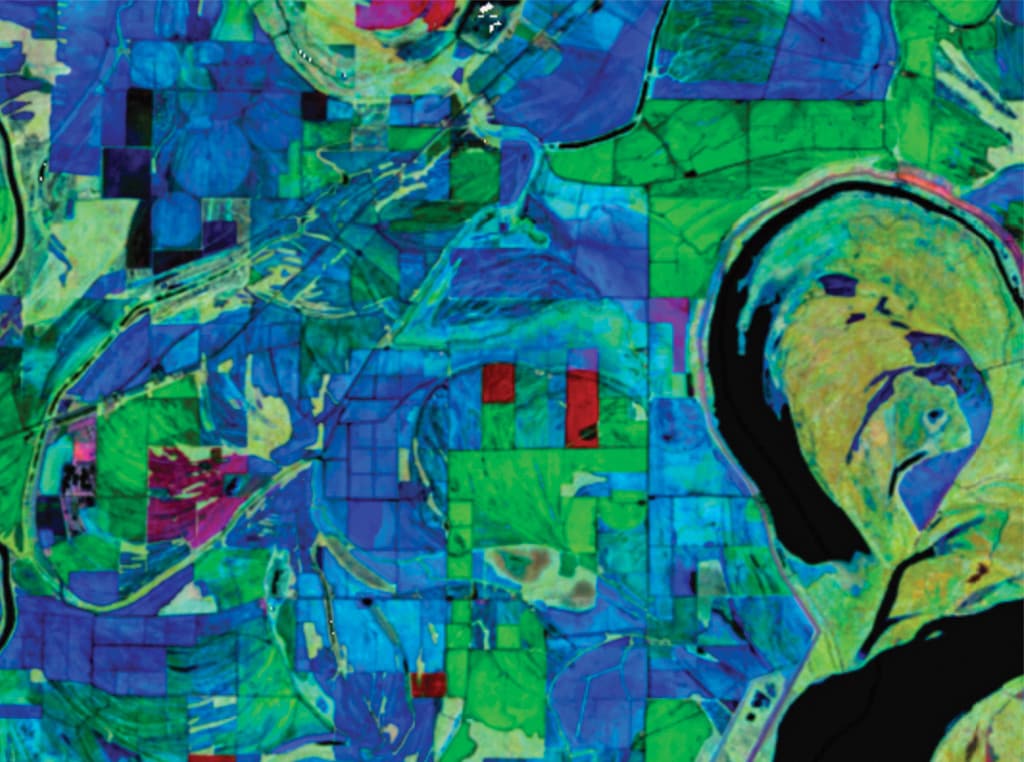

Ag Data Is Beautiful

Digital sattellite data paints farm masterpieces.

Agriculture, Specialty/Niche

Year-round Tourism

Muskoka farm develops innovative ways to incorporate four-season tourism attractions.