Koch says that oats is the most widely planted crop in Northern Ontario.

Agriculture March 01, 2021

Northern Potential

A warming climate has farmers flocking to Northern Ontario for opportunity.

Settlers didn’t have much luck trying to farm in Ontario’s Greater Clay Belt when they flocked to homestead the region after the First World War. The vast region, stretching from Hearst, Ontario to Amos, Quebec has very fertile soils but the climate left much to be desired. Disgruntled settlers described it as, ‘seven months of snow, two months of rain and all the rest is black flies and mosquitoes.’ Most only stuck around for a few years; those who stayed found work in the lumber camps and mines that sprang up in the area.

Warming dramatically. But a lot can change in 100 years. The region has warmed dramatically since 1990. Crop Heat Units at Kapuskasing rose from 2076 in 1990 to 2368 today. They are projected to rise to 2550 by the end of the decade and the growing season is expected to be 43 days longer by 2050. It’s on the cusp of becoming the land of opportunity for pioneering farmers. There’s a steady stream of them coming to the region from southern Ontario and the Prairies to seek their fortune.

“We’ve had lots of interest from primarily young farmers,” says Barry Potter, the agriculture development advisor for the Temiskaming Region with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA). “The main reason they’re interested in coming here is because of the availability of large expanses of relatively affordable land for beef. The climate is ideal for beef production too. We’ve lots of moisture to grow grass; the winters are cold but dry, so beef cattle can thrive in them without respiratory issues.”

The Greater and adjoining Lesser Clay Belts cover a vast area; 180,000 square kilometers stretching along Ontario Highway 11. Some estimate they could contain 29 million acres of arable land. The Canada Land Inventory identifies 4.4 million acres of them as class two, three or four in land suitable for cultivation. About 250,000 of them are now farmed.

Jason Desrochers’ family first moved to the Val Gagne, Ontario among the first wave of settlers in the 1920s. They’re one of the few still farming. Most left for work in the mills, mines and factories and never looked back. His father slowly built up his herd and expanded their land base while working at a paper mill in the region. Jason bought the herd and expanded it to 250 cow-calf Charolais/Simmental herd when he moved back from southern Ontario.

“Agriculture’s biggest potential is up here moving forward, Desrochers says. “There’s not as much opportunity in southern Ontario because they’re paving everything. Every farm down there seems to be divided by a highway, a road or a subdivision. This is likely one of the few spots anywhere in the world where you can still find large pieces of affordable land. Livestock whether dairy or beef do really well here. We have tremendous pasture and very good hay. Crops like oats, barley and canola do very well up here too. ”

Norm Koch’s arrival in the Temiskaming District in the late 1980s coincided with the start of a 30-year warming trend across the North.

The Desrochers have a land base of about 3500 acres, 2000 of them are cleared, about 300 are cropped and the rest are still bush. They feed cattle outdoors all winter. The most difficult part of raising cattle in the region is that the rainy summers make it difficult to put up quality hay. Desrochers says bale wrapping is a must. They are also taking advantage of government subsidies to tile drain as much of their land as possible to increase production.

Until recently they never bothered to clear land because it was cheaper to buy it than clear it. But that changed when prices jumped from $200 an acre to $1500.

“We’re now clearing land with the cows,” Desrochers says. “We bring in a dozer or a mulcher to clear two 10-12 acre areas each year. We divide the herd between the two clearings and bring in feed to them with the tractor every day. The surrounding trees shelter them from the elements so the cattle are quite comfortable; they’ve adapted to living in the bush. The seed in the hay sprouts the following year so it creates pasture at no extra cost. We’ve cleared about 100 acres this way so far.”

The warming climatic conditions are also encouraging much more interest in crop production across the region. It’s already had a dramatic difference in the types of crops being grown in the adjoining Lesser Clay Belt that extends down to New Liskeard on the shore of Lake Temiskaming. Norm Koch moved to Earlton, in the Temiskaming region in 1987 but had started buying land in the area in 1982. Today Koch with his sons, Rob and Chad, farms about 11,000 acres. They have a grain elevator and trucking division as well. Since he’s moved there, the CHUs in the district have jumped from 1800 up to 2500 in the summer of 2020. The main crops now grown in the region include oats, spring wheat, canola, soybeans, barley and some minor crops as well.

Jason Desrochers says that until quite recently it used to be cheaper to buy land than to clear it. That changed though when land prices in their region increased from $200 to $1500 an acre.

Droughts are rare in the region, but drainage can be a problem, Koch says. Tile drainage has made big farming operations possible. Fortunately, there are enough ravines, lakes and rivers nearby to make tile draining fairly simple. One of the biggest issues is competition for labour from the mines and lumber mills.

“There’s a lot of potential in this area and further north from here too,” Koch says. “At one point there was agriculture everywhere through the North. You can drive pretty much anywhere and find an old church or a 100-year-old barn. It wasn’t that farming didn’t pay back then, it was just that mining and forestry paid better, so the sons moved on. Now that land is more valuable, and you can grow good crops with tile drainage, people are clearing pockets of good land all the way to Hearst.”

OMAFRA and industry organizations such as Beef Farmers of Ontario have done a lot of preparatory work to produce spreadsheets so any producer who wants to come North and develop land would have an accurate idea what the costs are, Potter says. “We have built maps that show where land is available and accessible. If you’re considering coming North, you want to be prepared; those who take the time to do this usually are successful.”

Read More

Agriculture, Ag Tech

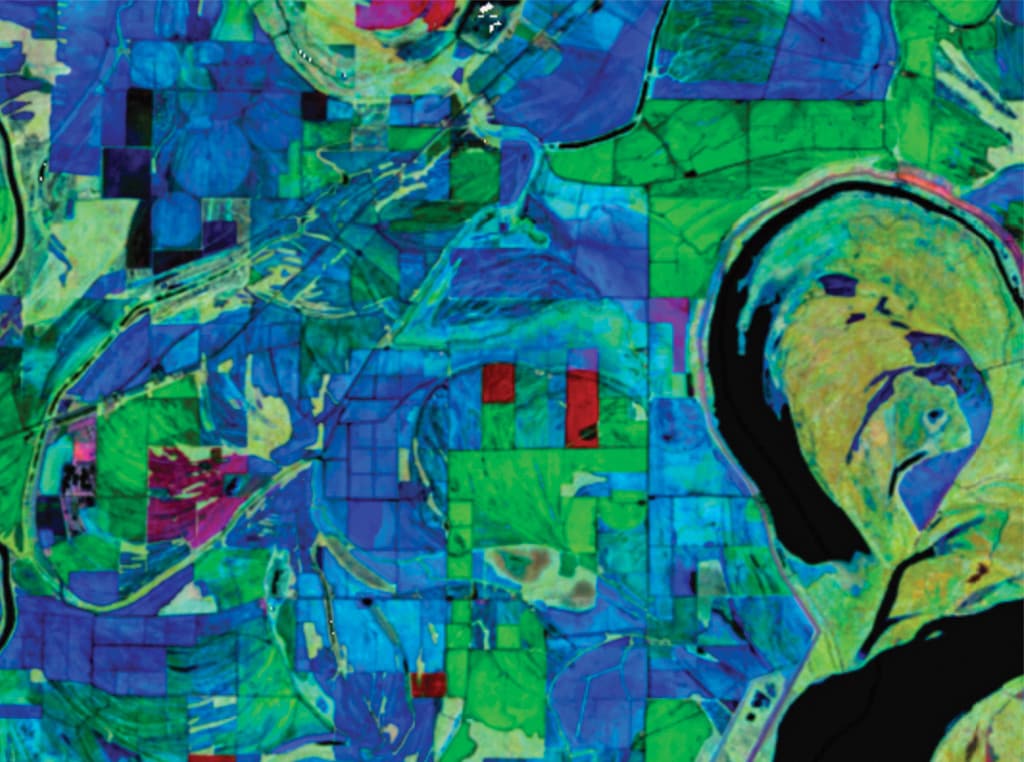

Ag Data Is Beautiful

Digital sattellite data paints farm masterpieces.

Agriculture, Specialty/Niche

Year-round Tourism

Muskoka farm develops innovative ways to incorporate four-season tourism attractions.