Agriculture, Farm Operation December 01, 2022

Bottling Success

.

Starting a unique bottling facility stabilized farm.

"When the price at the co-op is low, every farmer says they should bottle their own milk. But then prices go back up and they forget all about it," says Willis Schrock, owner of JD Country Milk.

Schrock and his wife, Edna, decided they weren't going to just think about bottling their own milk, they were doing it.

The first glass bottles of non-homogenized, low-temperature pasteurized, whole and chocolate milk clattered and clinked off the Russellville, Ky., farm-based line in 2006.

The decision to become a milk processor and marketer not only has provided work for five of their eight children, it kept the Schrocks milking. Kentucky dairies plummeted from more than 3,000 to less than 600 dairies since the Schrocks moved to Kentucky from Illinois in 1998. In a time when even more dairies are giving up, the Schrocks' business is growing. They've established a strong market and demand is on the rise.

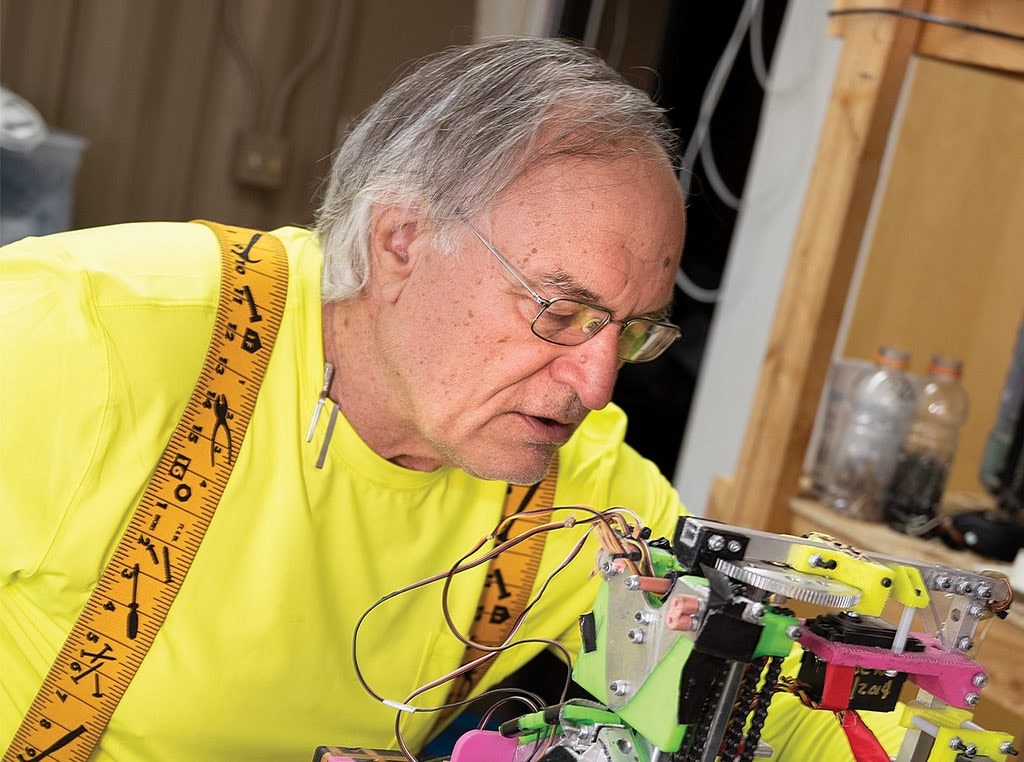

Above. Glass bottles and a unique product set JD Country Milk apart on the shelves. A deposit charged on the bottles is refunded if customers rinse and return. It's eco-friendly and the customer pays for the packaging. Willis and Edna Schrock started bottling milk to provide job opportunities for their children and grandchildren, including Stella (6) and Jayden (4) Borntrager who are already great helpers.

Building a base. Bottling alone doesn't ensure success. Willis aimed to create a unique, high-value product.

"We had to stand out. People are fascinated with the glass bottle experience, so we went with glass," he says. It also was ideal for their non-homogenized milk. Separated cream sticks to the sides of plastic and sours.

They opted for low-temperature pasteurization. Milk is heated to 145°F for 30 minutes, chilled and bottled. This process preserves enzymes degraded in high-temperature pasteurization, he says.

"It's as close to raw milk as legally possible. Our milk still clabbers if left on the counter. Some ethnic groups in our market don't even refrigerate it," he says. "People buy our milk to make yogurt and kefir or just to drink."

JD Country Milk has millions of potential customers in close range. They spent the first several years hitting the farmers' market circuit hard.

"We were in Nashville, Bowling Green, wherever Thursday through Saturday," he says. His son, Jeff, recalls working the stall and taking money at just 8 years old. "We got in some small grocery chains and after almost a decade we started getting calls from people wanting our product because of the quality. It was a long, hard drag."

Their products are now distributed in a 200-mile radius to Whole Foods, Sprouts and other high-end and natural grocery stores in Kentucky, Indiana and Tennessee. They've expanded to include strawberry milk, buttermilk, and supply ice cream base for artisan ice cream stores.

"We bottle on Monday. Starting Tuesday, five trucks are on the road each with their own route. More deliveries go out on Thursday and Friday," says Janette Borntrager, Schrock's daughter. She manages orders and the office when she's not milking cows with her husband, Luke, and their kids Stella (6) and Jayden (4). While several of her brothers handle trucking routes and help with bottling, Janette and Luke own the cows and sell their milk to JD Country Milk.

Herd balance. JD Country Milk needs about 100 cows to meet demand. For awhile, though, the dairy had no cows at all.

Initially, Willis refinanced the farm to buy equipment. He was milking 60 head.

"The co-op we were selling bulk milk to cut us off a month into bottling. They said we were competition," Willis says. He cut down to just 12 cows. Later that year, a storm demolished their barn. They stopped milking entirely—instead focusing on bottling using milk from two area dairies. "It was scary and things got tough."

In 2012 they were able to obtain value-added grants from the Kentucky tobacco buyout. The funds helped add a separator, bottle washer, more tanks and a building. Soon they were producing a robust line of products.

In 2019, Janette's family rebuilt the barn, bought cows and started milking again.

"We're at 55 cows and hope to build to 150 cows this winter. The goal is to provide all the milk for the bottling business," she says.

The herd allows her to support the family business without buying in directly. It provides an independent income stream.

"The satisfaction people have in our product is rewarding, but we do this for the money," Willis says. "Family farms are fun when they work, but we have to earn a living." ‡

Read More

AGRICULTURE, FARM OPERATION

Fast Feed

Ingenious self-serve bar streamlines winter feeding.

AGRICULTURE, EDUCATION

Cultivating Engineers

Engineer farmer brings high-tech science to rural kids.