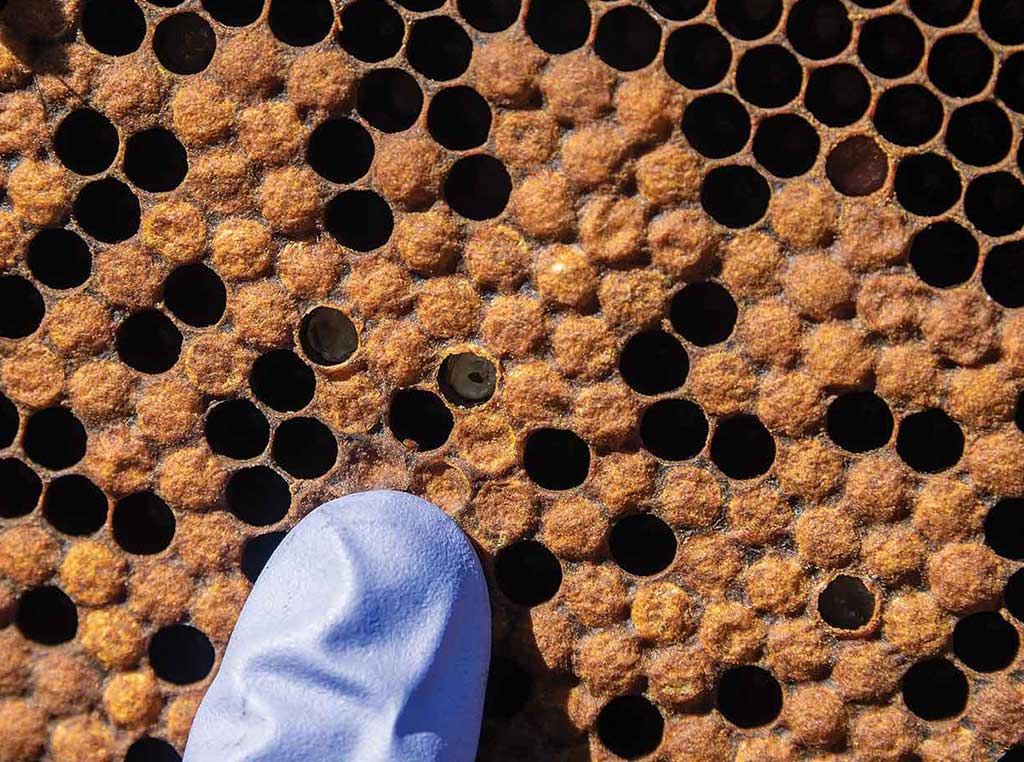

A varroa mite is visible in the “O.”

Specialty/Niche, Education June 01, 2021

Chilling Out

Busy worker bees don’t get much rest in their 5-to-6-week lifetimes. But the growing popularity of winter cold storage of bee hives gives a generation of bees a much-needed break, and could help beekeepers manage their top pest, the varroa mite.

What’s more, scientists are experimenting with controlled atmosphere winter storage and even summertime cold storage to heat up the battle against varroa.

Beekeeper Bud Wilhelm of Royal City, Washington, has overwintered his bees for the past 8 years, first in an apple storage building and more recently in a potato cellar. Last winter, he overwintered a total of 6,000 hives.

From an inputs perspective, cold storage is significantly less expensive than shipping bees and crews to California to overwinter at the edge of the Central Valley. Overwintering colonies in the outdoors require costly supplemental feeding with corn syrup and protein patties, as well as treatments with miticides and the labor-intensive shuffling of frames to consolidate colonies.

By contrast, bees in cold storage don’t forage or breed.

“That’s the biggest advantage to going into storage: you get that colony to shut down completely, so those bees aren’t wearing themselves out in a period where there’s no pollen and nectar to bring in to replenish themselves,” Wilhelm says. “The other major advantage is that when the hive goes broodless, the varroa mite’s reproductive cycle stops as well.”

Varroa mites lay their eggs on bee larvae and mature as the bee does. Without a bee larval stage, there’s no mite larval stage.

A winter brooding break may help explain how Asian bees kept varroa mites in check for millennia, Wilhelm surmises. Wild bee colonies go through a broodless phase during the short days of winter, he says, and Africanized honeybees—which are notably less susceptible to varroa than their domestic cousins—tend to pause for winter, too.

More effective. In hives coming out of cold storage, oxalic acid is more effective for varroa control than it is in outdoor hives, where young mites are protected by waxy brood caps, Wilhelm notes.

Rotating to oxalic acid’s mode of action and using cultural control to break the mite breeding cycle help extend stave off resistance to Apistan, the top miticide.

Entomologist Brandon Hopkins, a research assistant professor at Washington State University, is leading a study to explore whether a second broodless period in the summer may help further.

Many beekeepers have a gap between pollination contracts and honey production that could allow a few weeks of cold storage, Hopkins says. His hypothesis is that brief cold storage during that spring or summer window could trigger a broodless period and create another chance for a single, effective oxalic acid treatment rather than Apistan or the usual series of three oxalic acid doses.

Wilhelm wants to see more data before he tries it. He says summer bees are biologically primed to forage and raise brood, and fears they won’t thrive in an artificial winter, even a short one.

However, he’s already excited about another of Hopkins’ studies—letting bees’ respiration in storage drive up carbon dioxide concentrations to levels that the bees, but not mites, can tolerate.

“Having some alternative methods, like this work Brandon’s doing with storage and CO2 levels, plays into another tool in the toolbox of us beekeepers to be able to keep the mites at bay,” he says.

Orange-ish brood cap can shield varroa mites from miticides; a broodless period interrupts their life cycle and denies them protection. Entomologist Brandon Hopkins.

Read More

AGRICULTURE, FARM OPERATION

Keeping Command Of Each Kernel

Managing grain quality during drying and storage.