Rural Living December 01, 2020

Pickled Pink

New market opportunities are bubbling up thanks to consumers’ interest in fermentation.

Christopher and Kirsten Shockey started out on their 40-acre homestead back in 1998 milking cows and goats, but talking to them now, it’s clear that their herd has grown much, much bigger—billions of microbes pickling and fermenting their bounty.

“I think of them as millions of tiny chefs,” says Kirsten, who, with Christopher, has introduced thousands of people around the world to the wonder of fermentation and pickling through their books, lectures, and online videos. “People are discovering the magic of microbes. And the beauty is, it’s this process that can be applied to everything.”

For the young couple, settling in southwest Oregon’s Applegate Valley was a dream come true: growing their own food on a permaculture farm, homeschooling their kids, working together as a family. They planted their denuded land, added a commercial kitchen to the house, and made a go of it. But the reality of trying to eke crops out of their dry, forest soils and old apple orchard hit them hard. They couldn’t produce enough vegetables to sell or grow enough apples to make cider commercially.

Still, they smelled an opportunity. Kirsten’s mother had started the couple on making sauerkraut at home, and they realized fermentation could add the value they needed.

“I had made sauerkraut and I had made homemade cheese,” Kirsten recalls. “We figured, ‘let’s make sauerkraut. You can’t kill anyone with that.’” They started fermenting commercially in 2002, set up shop at a local farmers’ market, and built a following.

They also built a model that can work for many farms, says Christopher, especially in states like Oregon, with farm direct laws that allow farmers to ferment a reasonable amount of their farm-grown produce before having to get food processing permits.

“Now they can create a product that’s much more stable,” he says. “In the beginning of the year, when all they have is radishes, they can say, ‘here’s something pretty.’ At the end of the year, when we’re played out of fresh vegetables, you look and say, ‘oh, that sounds good.’ That helps the farmers stretch that season and helps them capture that value, and they can balance out their labor.

“For people that are wanting to start food businesses, especially small food businesses, this is an avenue to create something that’s got great flavor and local terroir,” Christopher adds.

Focus shift. Over time, the demands on the Shockeys were growing. They started buying cabbage from neighboring farms, spending long hours slicing heads and massaging salt into leaves, and hosting more and more visitors to the farm eager to learn the art of fermentation.

Pressure was increasing to upsize their sauerkraut production, something the Shockeys were ambivalent about, especially without enough local cabbage to feed their growing demand. Around the same time, two of their kids had moved on to college, freeing up some of Kirsten’s time.

They decided to shift their focus to the growing demand for education. A neighbor took over the sauerkraut business and the Shockeys wrote their first book, Fermented Vegetables, in 2014 and launched Ferment Works.

Fermented Vegetables has been translated into German, Polish, Italian, and Spanish, and has sold more than 200,000 copies. It also generated invitations for the Shockeys to take their pickle evangelism on the road.

“The Germans think it’s so funny—two hippies from Oregon are teaching them how to make sauerkraut,” laughs Christopher. “Sometimes you need an interloper from somewhere else saying, ‘that’s pretty cool; let’s put it in this and see what happens.’”

The Shockeys have been feeding the hunger for fermentation knowledge with a steady stream of books—four so far—covering vegetables, fermented hot sauces, Asian-style bean fermentations like miso and tempeh, and hard ciders and vinegars.

They are dyed-in-the-wool teachers, a passion that clearly extends to fermenters of all ages. Christopher lights up as he spitballs about presenting microbes as superheroes (complete with caped uniforms) and gleefully describes fart jokes that sneak a big dollop of biochemistry into the couple’s pickling classes for kids.

When the pandemic shut down their live classes, the Shockeys launched online courses at https://ferment.works. The website is also packed full of encouraging fermentation information, including a troubleshooting section that seems tailor-made for calming midnight panic attacks in the kitchen. You quickly get the sense that the Shockeys have seen it, done it, and found an answer. They want you to know it will all be OK in the end.

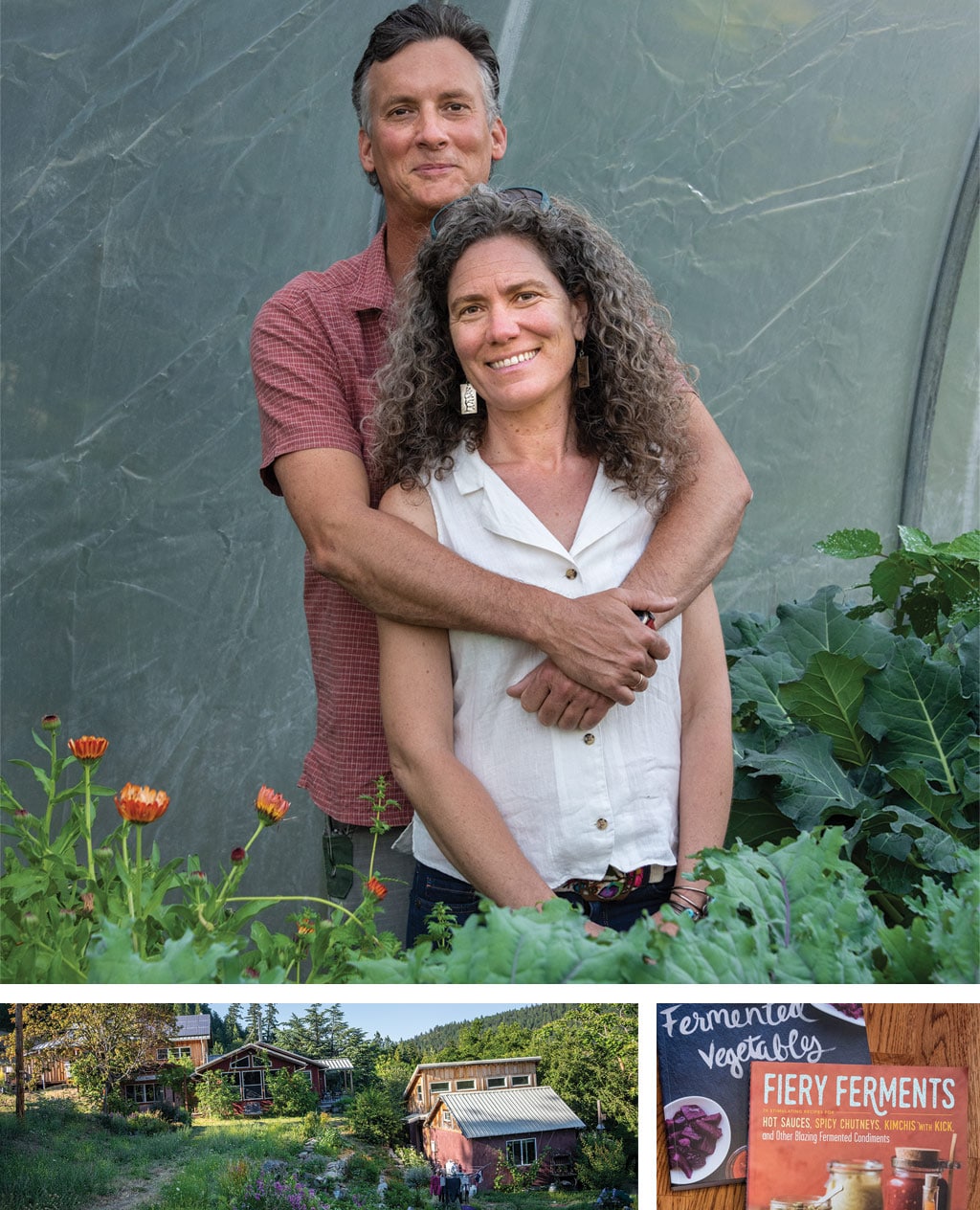

Christopher and Kirsten Shockey have taken their enthusiasm for fermentation worldwide. The Shockeys have written four books so far; their first sold 200,000 copies worldwide.

Enthusiasm. The Shockeys’ books are fun, friendly, and demystifying, a great reflection of their abundant enthusiasm for inviting people into the world of fermentation and dispelling their fears.

While Miso, Tempeh, Natto details the precise environmental control needed for Japanese-style ferments seeded with an Aspergillus-innoculated rice called koji, the Shockeys’ latest book, The Big Book of Cidermaking, unleashes the power of wild yeasts.

Whatever the medium, the Shockeys’ message is simple: in contrast with canning, which requires strict sanitation, fermentation thrives in an environment that’s simply clean and free of oxygen. And though there’s a lot of chemistry going on, the only testing equipment needed is your five senses.

“It’s flavor-based,” says Kirsten. “Once the acidity is 4.0, once you’re tasting the acidity, you’re golden. Once it tastes pickle-y, it is pickle-y.”

More nutrients. The Shockeys have a special love for cider; Kirsten calls it “time in a bottle.”

“The last bottle forces you to ask, ‘hey, what were we doing then?’ It’s adding time to the terroir,” she says.

She is even more passionate about the health benefits of fermented foods. Unlike canning, which makes food shelf-stable by killing organisms that can cause it to decay, fermentation creates an environment where beneficial microbes can transform produce into shelf-stable food—and improve it.

“You’ve picked it right at the peak of its freshness and the peak of its nutritive value, and you’ve fermented it,” she says. “So you’ve not only captured that peak, you haven’t killed any of it. Then the microbes actually bring the nutrient level up. You’ve got digestive enzymes that are going to help you process your whole meal that you’re eating with it. And the microbes have digested some of this vegetable that you wouldn’t digest anyway, so now your body can uptake those nutrients. It’s pretty fantastic.”

Dozens of vinegars are culinary works in progress on shelves in the Shockeys’ kitchen.