Sustainability March 01, 2024

War on Waste

.

Turning waste into energy is just the start for the Divert team.

At the Stop & Shop Distribution Center in Freetown, Massachusetts, reusable bins of wasted food are lined up at the Divert wasted food-to-energy facility. The place is clean and smells much more like vegetables than trash. And it looks like the future—a more efficient future.

Broccoli and bananas, cookies and chips...days or weeks ago, they all made the trip from the vast distribution center to 223 Stop & Shop and Central Fresh Kitchen locations across New England. Now the unsold food is back to be processed by Divert into enough renewable electricity to supply about one-third of the distribution center's needs.

"On a daily basis, that's 70 tons of food that's not going to a landfill," points out Divert's plant manager, Corey Sanders.

It's a grind. Each bin is weighed and dumped into a grinder that separates out plastics, cardboard, and large, fibrous food for disposal. The remaining food slurry spends about 1.5 days working its way through a continuous-flow anaerobic digestion process. It's not unlike the digesters that have become familiar sights on many dairy and hog farms, where they turn manure into natural gas.

But because food waste can vary in composition and pH, it makes a stop in a 100,000-gallon holding tank, where loads of slurry blend into a more uniform mix. As the microbes in the 1.2-million-gallon digester downstream start to speed or slow their methane production, plant operators adjust the flow of slurry to keep the gas output consistent.

After the microbes—which were seeded when the plant opened in 2016—have done their magic, the methane is chilled to de-water and concentrate it. Then it's piped into a generator where it is turned into electricity.

It's a pretty simple process. But the problem of food waste is both complex and huge. That's where Divert has set its sights.

Food waste—63 million tons of it per year in the U.S.— accounts for one-third of America's landfill volume, and that space is dwindling fast. Estimates range from 17 to 60 years before the U.S. runs out of landfill capacity.

Fueled by contracts with many of the nation's biggest grocery chains and a $1 billion infrastructure development agreement, Divert is expanding its footprint to 30 facilities. That will put the company within 100 miles of 80% of the U.S. population by the end of the decade, says Ben Kuethe, vice president of customer solutions and success.

New, integrated sites coming online this year in California and Washington will collect store-specific data on wasted food to help improve waste reduction and donation efforts. Results will help retailers and food recovery agencies improve their processes. For instance, Divert analysts have already documented the impacts on shelf life when food deliveries get stuck on loading docks. They also spotted a design error in a high-value packaged product that was confusing shelf stockers and customers, leading to premature disposal.

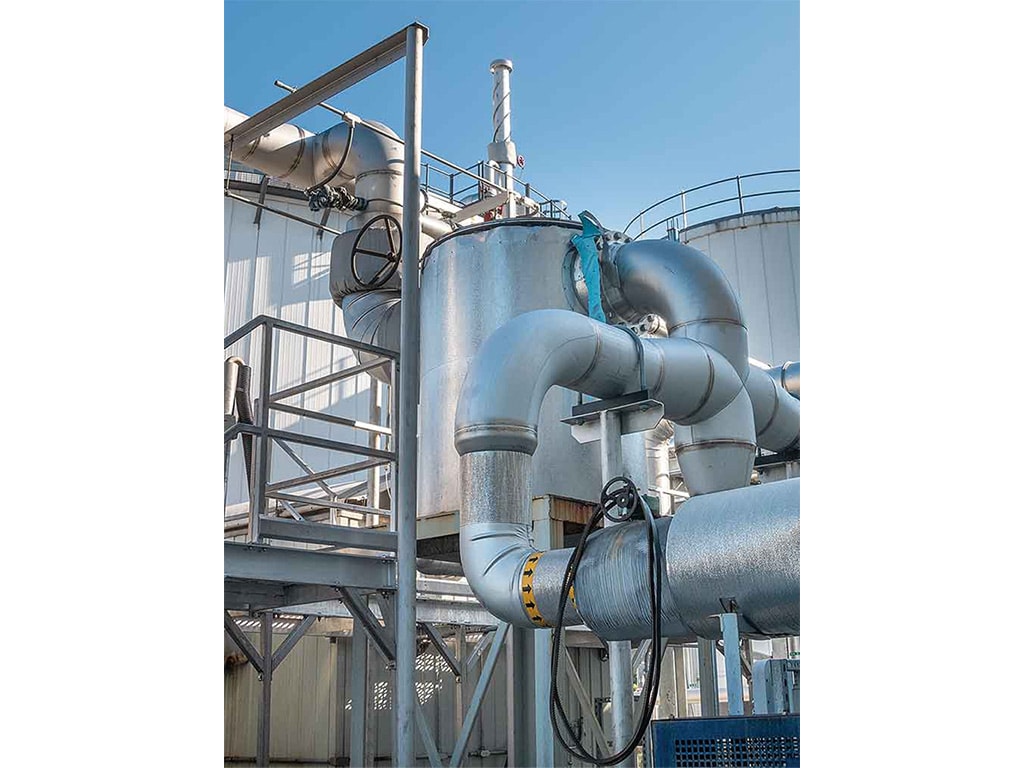

Above. In Freetown, wasted food is weighed, processed (first image), then digested into biogas that runs a generator on-site. Other Divert facilities also analyze returned food to prevent or reduce waste.

Strong case. In New England, grocers pay about $150 per ton to landfill their waste, says Kuethe. In Seattle and California, fees run $200 or more, while costs in the Midwest run $30 to $50 per ton. That makes a strong business argument on the coasts to cut waste just to reduce disposal costs. But Kuethe points out that many corporations' interest in reducing their carbon footprints—and improving their bottom lines—are building an even stronger case nationwide.

"About $400 billion worth of food is grown, distributed, then wasted," he says. "If you're able to prevent waste, that has a pretty significant impact from a climate perspective. And from a socioeconomic perspective—how we keep the cost of food down—prevention has a much bigger impact."

While Divert focuses on food retailers now, farms could benefit as integrated plants spread.

"That infrastructure allows us to figure out what the solutions are for other food waste generators in the region, whether it be farms, distributors, wholesalers, restaurants, and more," says Kuethe. "Then it's just logistics." ‡

Read More

AGRICULTURE, LIVESTOCK/POULTRY

Easy Keepers

Sheep, cattle, and more on an Oregon homestead.

AGRICULTURE, EDUCATION

Breakfast on the Farm

Start your day learning about farming.