In the vast expanse of range making up the Flint Hills of Kansas, it can be difficult to track cattle. Virtual fence technology, which uses GPS-enabled collars combined with cellular towers, helps beef producers manage grazing areas, locate herds, and set boundaries to protect waterways and protected species.

Agriculture, Ag Tech January 01, 2024

Wire-free Fences

.

Virtual fences allow customized grazing.

Good fences make good neighbors. That's especially true when one neighbor is Mushrush Ranches, the other is The Nature Conservancy, and they both are located in Lesser Prairie-Chicken habitat.

Mushrush Ranches leases pasture from The Nature Conservancy, which co-manages the 10,000- acre Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve near Strong City, Kansas. It is the only national park dedicated to the tallgrass prairie, which represents a slice of prairie that once stretched from Nebraska to Oklahoma. The Nature Conservancy manages the tallgrass prairie ecosystem using prescribed burns and bison—the same system used prior to the introduction of barbed wire and cattle grazing generations ago.

The Nature Conservancy also conducts research on protecting populations of the Greater Prairie-Chicken, a near threatened species indigenous to the high-quality Flint Hills tall-grass prairie.

The organization and Mushrush Ranches are using a virtual fence system from Vence, an Australian company that was acquired by Merck Animal Health in 2022, to control cattle movement and learn how grazing practices influenced by virtual fence affect vegetation, soil health, and grassland bird habitat, says Tony Capizzo, Flint Hills Initiative Manager of The Nature Conservancy.

Using Vence, the Mushrushes are being asked to establish grazing boundaries around prairie chicken habitat, avoiding these areas during mating season.

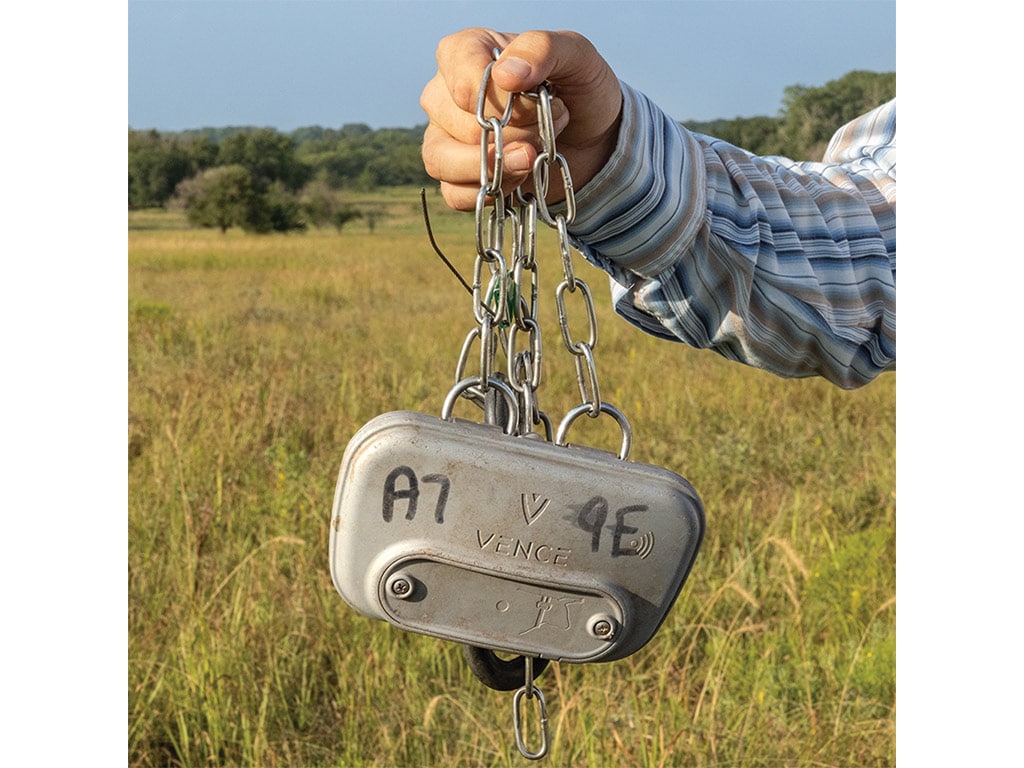

The Vence ecosystem requires cattle to wear a collar containing a global positioning system chip and magnetometer. If an animal goes near a boundary pre-set by the rancher, the collar emits first a buzz, then a shock if they stroll outside the boundary.

Ranchers must use an FM tower that transmits a signal from the collar to a smartphone, allowing them to keep tabs on the herd whereabouts at all times.

Above. Digital fence technology helps the Mushrush family fine-tune grazing management in the Kansas Flint Hills, says Cole Mushrush. Pre-programmed boundaries are set by operators, and cattle wear these GPS-enabled collars around their necks. A minor electric impulse keeps cattle within the boundaries, Mushrush says.

Checking in. The Mushrushes have each collar "check in" with a tower twice per day, which prolongs battery life. In turn, they check collar status on a smart phone or computer. The collars are always live, keeping cattle where the Mushrushes intend.

The GPS signal has a roughly 30-foot buffer.

"That works pretty well when you're trying to just kind of phase into an area and not create any hard lines," Mushrush says.

That phase effect works well for the Nature Conservancy project. Prairie chickens don't thrive in tall, dense thickets of vegetation; nor in areas that have been grazed to short heights. "You want different stratifications, because different birds use different heights of grass," Mushrush says. "That's kind of the goal, to promote patchiness."

The Nature Conservancy and Mushrush Ranches are in the second year of the study, and both sides appear to be showing wins. Bird habitat is improving in areas managed by virtual fence. And, Capizzo says areas of range affected by erosion or over-grazing are healing, thanks to the ability to manage boundaries.

Goals for the Mushrush family are different. They aim to improve grazing efficiency, and use the virtual fence to encourage more grazing on hill slopes, which typically are not well utilized by cattle.

And they see improvements in the Flint Hills ecosystem, Cole adds.

"Plant diversity with different forbs and grasses is always better. Having the birds on the range is just showing that our ecosystem health is where it needs to be," Cole says.

Learning pains. Virtual fence collars are not failsafe. There is a four-day training protocol, which Mushrush says is essential to follow. And, each of the last two years, the Mushrushes have had collars short out due to water; they also have come detached from the chain that holds them around the cows' necks.

"When less than a third of your herd is following it, and none of them do, it's effectively zero," the rancher says.

The virtual fence industry is in its infancy. Additional companies are producing their own products, which will be good for ranchers.

"In the next 10 years, I think this technology is going to be crazy good," Mushrush says. ‡

Read More

AGRICULTURE, FARM OPERATION

Resilience Man

How Ron Rosmann adjusts Rosmann family farms to economic and climate changes.

RURAL LIVING, EDUCATION

Odd Hours, No Pay, Cool Hat

Volunteer firefighter numbers are declining rapidly across the United States.