Agriculture, Education September 01, 2023

Smoke and Substance

.

Breakthroughs promise answers to wine taint questions.

The effects of wildfire smoke on wine quality can range from subtle smokiness to profoundly ashy flavors—called "smoke taint"—and economic devastation from sub-par wine or broken contracts. The problem is, experts can't yet predict how a cluster of grapes or barrel of wine will react to smoke exposure. Smoke taint is a needle in wine's complex molecular haystack, a needle that can appear, disappear, and re-appear as wine ferments and ages.

Right now, smoke taint is impossible to fix without also removing molecules that give wine its flavor, color, and mouthfeel.

Fortunately, an $8 million research project has pulled together Oregon State University (OSU); Washington State University (WSU); University of California, Davis (UC Davis); and more. That dream team is zeroing in on several thiophenol compounds, or thiols, that appear to increase in grapes exposed to smoke at certain stages of fruit development. Understanding the reaction of grapes to smoke and tracking the metabolism, binding, and solubilization of thiophenols could yield valuable insight into how to deal with smoke-exposed grapes.

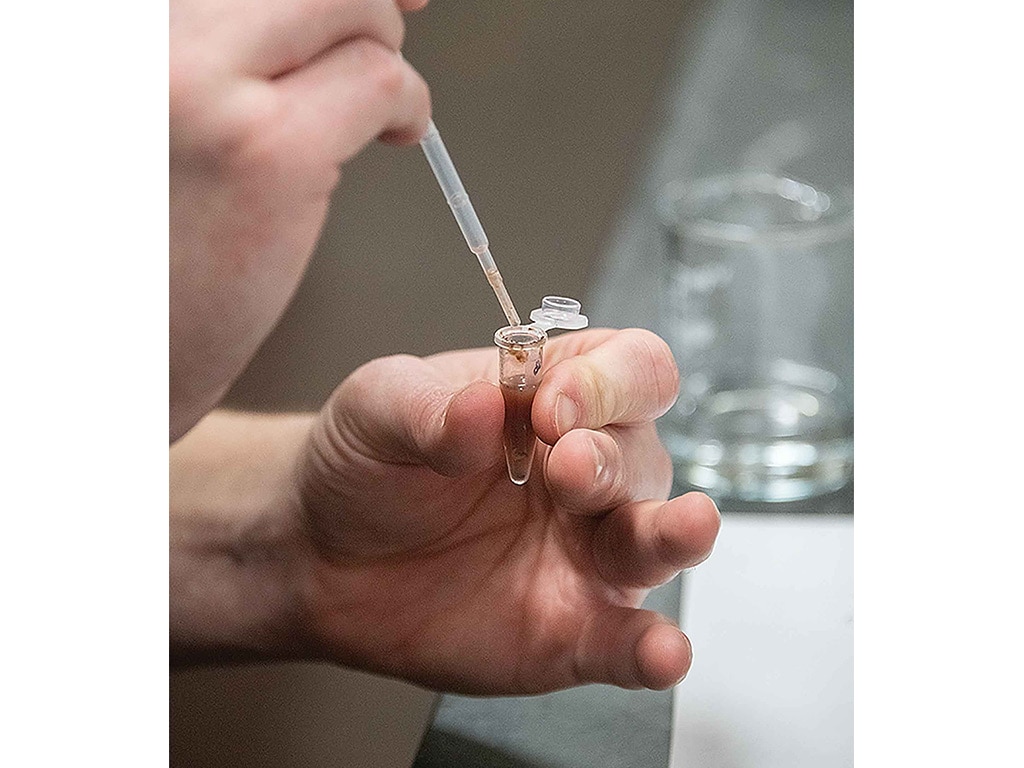

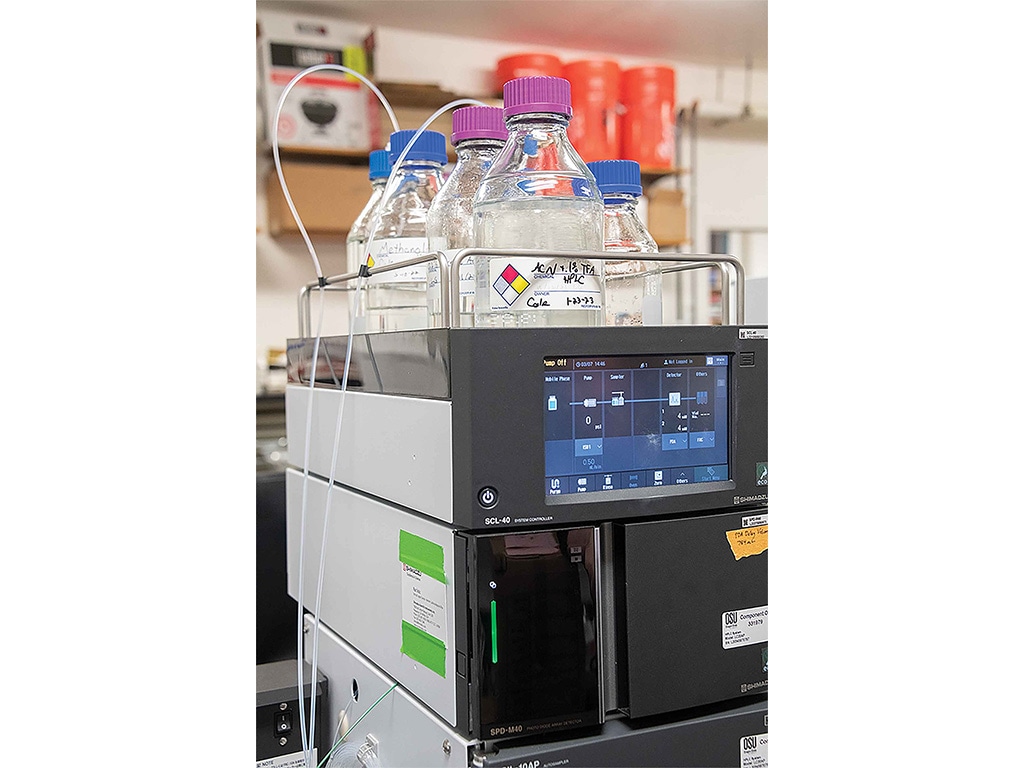

Above. Post-doc Cole Cerrato prepares a sample for analysis at Oregon State University. Elizabeth Tomasino in her lab at Oregon State. A researcher sprays grapes with protective film. A barbecue grill pumps smoke in an Oregon winegrape smoke trial. Analytical chemistry is key to understanding smoke taint.

Decision tools. It's a massive effort to address a complex challenge likely to become even more common. Over the last 40 years, wildfire acreage in the West has jumped 300%, and Harvard researchers predict a further 54% increase by the 2050s. The industry needs guidance.

"What we're primarily trying to work out is a big system of, 'if you have this measurement of smoke in the air, you shouldn't pick your grapes,' or 'you should pick your grapes, but you'll have to do something different with them, and here's what you can do so you can get it below the level where you'll perceive this really negative aspect'" says OSU's Elizabeth Tomasino, project c0-leader with Anita Oberholster of UC Davis and Tom Collins at WSU.

Tiny amounts of thiophenols like thiocresol or thioguaiacol can boost dark fruit or floral flavors in wine, but larger volumes, especially combined with volatile phenols, can taste like smoke, bacon, or cigarette ash to many people—even at hundredths or thousandths of a part per billion.

"For thiols in general, a little drop in a swimming pool is all you need to get an effect," Tomasino explains. "We're doing a lot of work on, 'what's the number in wine that tastes bad?' We're also linking that eventually to, 'what's the number in the grapes?''

Part of the problem with smoke taint is that the offending compounds can hide in ripening fruit.

"The smoke compounds actually diffuse into the grape," Tomasino says. Once that happens, they get attached to the sugars and they're not flavor-active anymore, so you can't taste them. Then during winemaking, with winemaking conditions and enzymes and yeast, they get released from what they're bound to, so all of a sudden the wine starts smelling really smoky or you taste it and it's like a mouthful of cigarette smoke."

To head off surprises in the fermentation tank or bottle, the multidisciplinary team is comparing air quality models to thiophenol concentrations in grapes and smoke taint in wines. They're burning barley straw with radioactive tracers to track the fate of smoke components through the grapes and wine, and lighting up other materials to compare the chemical makeup of various kinds of smoke. They're testing cellulose nanofiber coatings to see if they can prevent smoke from entering grapes (two of the barriers show promise so far, says Tomasino). And they are putting tracers into sulfur sprays commonly used for disease control to see if they increase the amount of thiophenols produced in smoky years. Finally, Collins' team at Washington State University is exploring the genetics of grape vines that metabolize smoke compounds in various ways to see if there might be a breeding or enzyme regulation component to the issue.

"It'll take some time, but when there's a smoke event, you'll know what to do at different points in the process, so we won't have the blind panic that tends to happen now," says Tomasino. ‡

Read More

SPECIALTY / NICHE

Age in Place

How can you change your home to be senior-friendly?

SPECIALTY / NICHE

Flowers with Flair

This duo uses flowers to bring smiles to customers.