Agriculture, Education December 01, 2023

Golden Opportunity

.

The Gold Rush launched California's modern agriculture industry.

Gold! The word alone conveys an electric thrill. The story of James W. Marshall's 1848 discovery of gold in the tailrace of the sawmill he was building for farmer John Sutter focused the world's attention on California and propelled it from a sparsely populated backwater to an economic and agricultural powerhouse.

At the time of Marshall's discovery, 150,000 Native Americans, 6,500 Mexican or Spanish residents, and 800 Anglo settlers lived in California. Agriculture was largely limited to gardens and orchards around Catholic missions, subsistence farms, pockets of orchards and vineyards, and cattle and sheep on huge Spanish and Mexican land grants called ranchos.

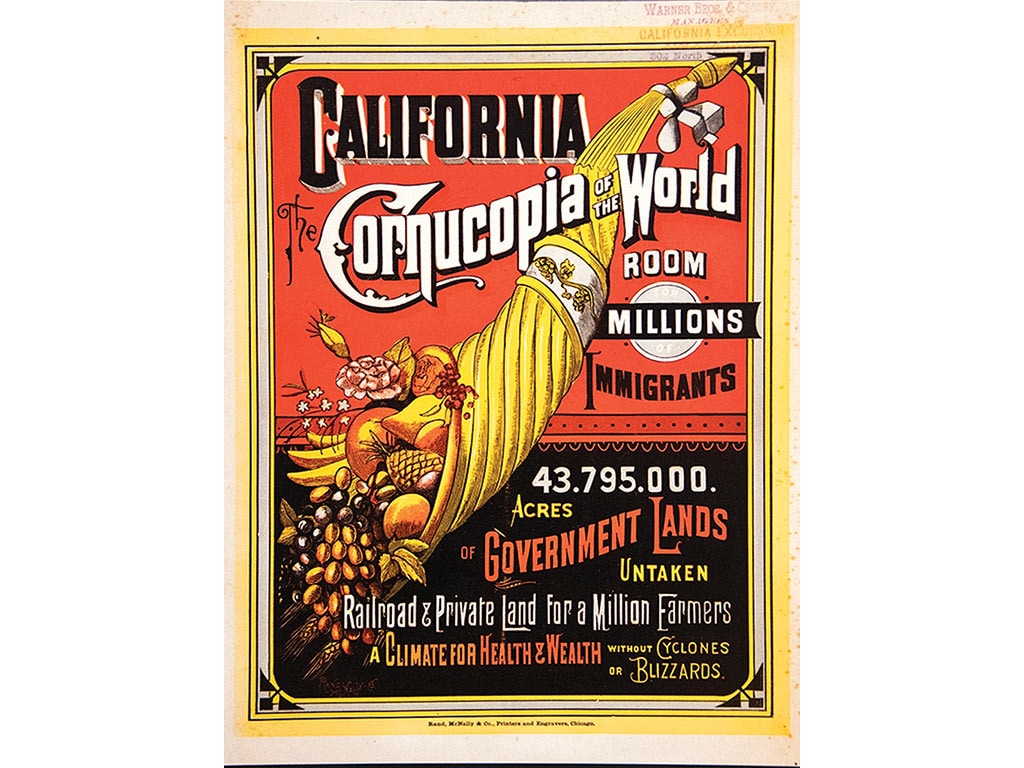

In less than two years, the non-Native population jumped by 100,000, and by the mid-1850s the influx totaled more than 300,000. By 1890, California's population crossed the 1-million mark.

At first, feeding the swelling state was a matter of imports. Beef and lamb from local ranchos was supplemented by cattle and hogs driven from Missouri, Texas, and Nevada. Eastern shippers sent canned fruits and vegetables, as well as oysters, fish, and dried meat. Oregon farmers supplied apples, wheat, and flour, while more wheat and flour poured in from Chile, Peru, and Australia. Farms in Hawaii and Tahiti shipped fruit, vegetables, white potatoes and sweet potatoes, and sugar. China sent rice, fish, and tea. In all, more than 1,000 boats called on San Francisco in 1849.

Above. Mission San Gabriel in today's Los Angeles metro area was home to California's first citrus orchard, as well as figs, grapes, peaches, pears, and more. Some '49ers—California Gold Rush migrants—collected planting stock there. This Placerita Canyon creek was the site of an 1842 discovery that presaged the Gold Rush. Barry Zoeller at Tejon Ranch. Two million gallons of water per minute cross Tejon Ranch through a State Water Project easement.

Fancy food. Demand was fueled by thousands of hungry, single men making money. Unlike loggers and railroad workers, miners had a taste for fine food and demanded the opportunity to choose where they dined, rather than settling for room-and-board packages. That created a vibrant restaurant culture in mining towns and huge demand for luxury foods like oysters, jams and jellies, wine, and brandy. Scurvy was common among miners, so fruits, vegetables, and pickles were especially coveted.

As a result, it's little surprise that in Gold Country, potatoes, onions, and oranges sold for $1 apiece ($39.70 in today's money) or more, and that stewed vegetables were sold by the forkful.

It didn't take long for new Californians to spot the opportunity. According to California State University, Chico historian Joseph R. Conklin's Bacons, Beans, and Galantines, miner Edward Austin wrote his brother in 1849 asking for vegetable seeds. He figured a 10-acre plot could return $80,000 in a season—$2.8 million today.

Conklin also told the story of the wife of Peter Wimmer, one of Sutter's employees in Coloma. Demand for her peaches was so high that Mrs. Wimmer sold them in advance, tagging each blossom with the name of its buyer.

Farm shift. Farming in California required some major adjustments for transplanted Eastern growers. The Mediterranean climate of wet winters and rainless summers took some getting used to. So did mild winters, which inadequately chilled Midwestern winter wheat varieties but allowed Spanish varieties like spring Sonora White and club wheats to thrive when planted in the fall. And learning to evaluate California soils took practice.

Even so, by 1854, California wheat farmers were producing a surplus and shipping grain to Britain. Apples, pears, potatoes, and vegetables popped up in the Sierra Foothills near the camps and in the sprawling grasslands and wetlands of the Central Valley. Towns like Marysville quickly became renowned for their produce.

California's economic balance tipped when an 1884 court decision settled a raging battle between miners and farmers. The first few years of the Gold Rush was fed by placer gold, flakes and nuggets panned from streams. In 1853, efforts began shifting to hydraulic mining, industrial-scale blasting of hillsides with high-pressure hoses. Choked rivers and mudslides from hydraulic mines flooded valley farms with silt, and farmers sued the miners.

The ruling prohibited mining companies from dumping debris into rivers and streams. The decision reflected the growing importance of California agriculture, and has been called the state's first major environmental law.

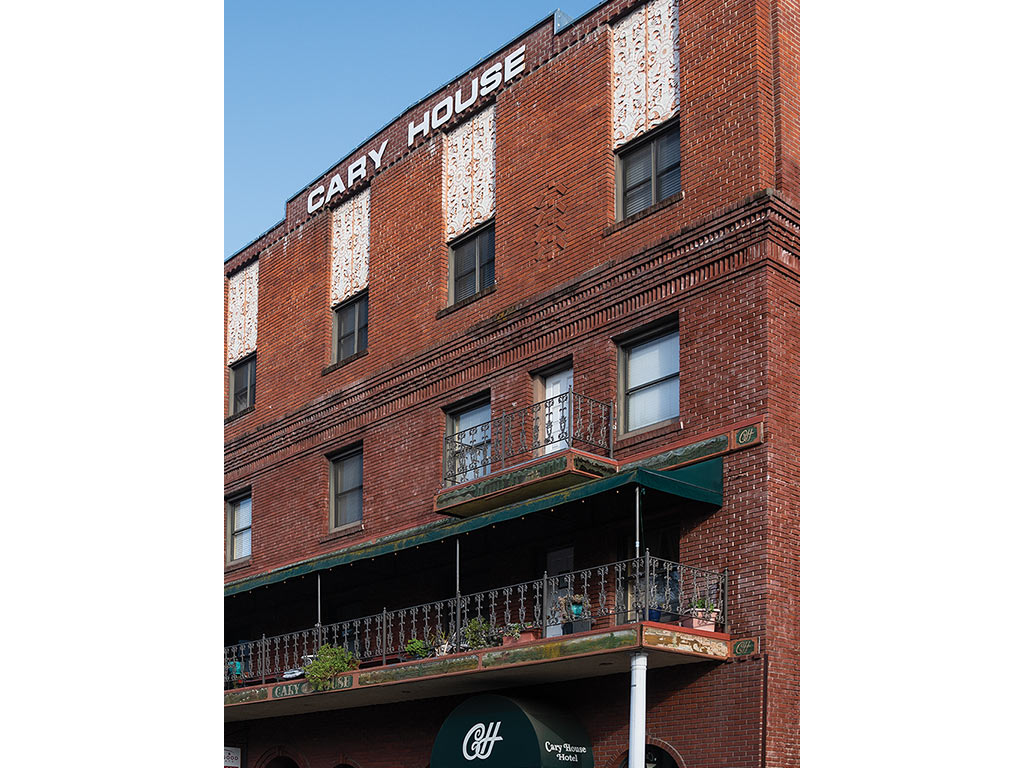

Big Cut, a massive hydraulic mining scar, is still visible from Boeger Winery in Placerville, California. When Big Cut was being blasted in the Sierras, El Dorado County was the third-largest wine producer in California, with more than 2,000 acres in vines.

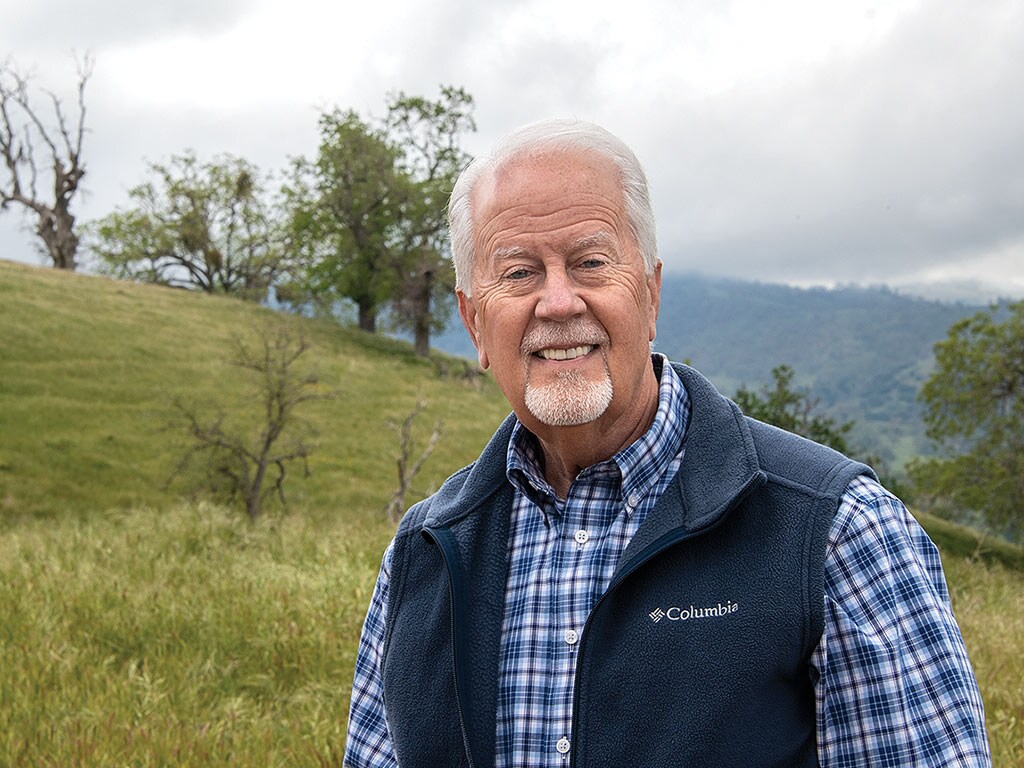

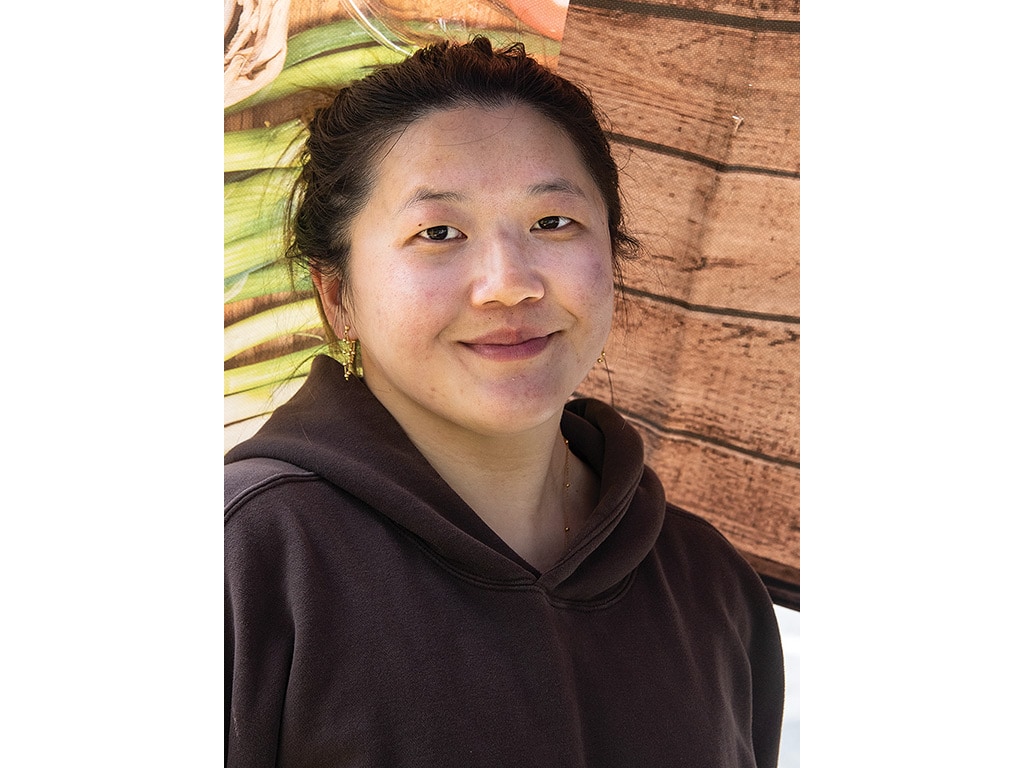

Above. In 1872, Giovanni Lombardo built this winery to sell wine to miners. Today it's the heart of Boeger Winery. Greg (left) and Justin Boeger helped restore the Sierra foothills' wine industry. At a miner's request, a chef at the Cary Hotel in Placerville created Hangtown Fry, an omelet of the era's most expensive ingredients: eggs, oysters, and bacon. Cindy Xiong farms vegetables in Marysville, which has been famous since Gold Rush days for its produce. During the Gold Rush, onions fetched $1 apiece ($39.70 today) or more. So did fruits and vegetables that warded off scurvy. Gold Rush fortunes, irrigation, and the transcontinental railroad boosted California agriculture by the 1870s.

Wine boom. Greg Boeger points out the cut from a block of grapes he discovered under a thick stand of blackberries and poison oak. The vines were probably planted in the 1870s or '80s by the Lombardo/Fossati family, who farmed the property from 1863 until Boeger bought it in 1972.

Back then, Boeger was a recent University of California, Davis grad from an old Napa grape-growing family looking for a place he could afford to start a vineyard. He and his wife Sue turned out to be pioneers, rekindling El Dorado County's wine heritage. The area had shifted to pears during Prohibition—about the same time intensive crops like fruits, vegetables, and nuts eclipsed grain in the state's earnings. But by the 1970s, El Dorado pear orchards were folding due to disease and market pressures.

"As pears phased out, the ag community, and the ag commissioner in particular, wanted to find a new crop so that everything didn't go into subdivisions that were moving up from Sacramento," Boeger recalls. "So with the University of California, Davis, they planted six experimental vineyards in the '60s. The wines were pretty spectacular.

"When we came to El Dorado County, there were six acres of vineyards," Boeger says. "But after the 50 years we've been here, now there are again about 2,400 acres of vineyards and 60 wineries, which is exactly what there was during the Gold Rush."

Perhaps no farm tracks the California Gold Rush story better than Tejon Ranch. Assembled from four Mexican ranchos by Edward Fitzgerald Beale—who rode and sailed to Washington, DC, to deliver the news of the Sutter's Mill discovery—its 270,000 acres started as cattle and sheep range. When irrigation systems were built on the shoulders of the mining industry's water know-how, Tejon Ranch planted citrus, peaches, and annual crops.

Beale's son sold the ranch to southern California investors who eventually took it public. Today, 14,500 cattle still graze the slopes, while cropping includes almonds, pistachios, and winegrapes. The ranch is home to commercial and residential development, oil and gas, limestone, a water right-of-way for the State Water Project, and a conservation agreement restricting development on 90% of the land. The ranch even hosts film and TV shoots for Hollywood, a short drive away.

In short, the 1868 Tejon Ranch brand is stamped on a microcosm of California's farm history.

"We're guided by two principles: stewardship—take care of the land—and use the land to meet the needs of the people," says Barry Zoeller at the ranch offices in Lebec. "We believe we've demonstrated that you can do both. They're not mutually exclusive."

At an entirely different scale, Cindy Xiong and her family pack a wide range of fruits and vegetables onto eight acres in Marysville. Cindy sells them at farmers' markets in Grass Valley, Marysville, and Yuba City, all towns established during the Gold Rush.

From Yukon Gold and russet potatoes in the spring through summer crops of tomatoes, cucumbers, hot peppers, to fall sweet potato harvest, Xiong Family Farm produces "literally anything you can grow," she says.

Legacy. Some historians mark the end of the Gold Rush at the shift to industrial mining, when individual panning gave way to mining for wages. Others use the 1884 court ruling, or the shift of attention to World War I.

But the legacy remains. Competition for labor with the mines influenced California farmers' adoption of mechanization and technology. Water and logistics expertise developed for gold boosted agriculture. So did fortunes made in the gold fields and invested in local farms.

It's poetic that James Marshall, whose discovery kicked off the California Gold Rush, didn't get rich as a gold miner—but he did settle down to farm. California agriculture may have turned out to be the biggest bonanza of all. ‡

Read More

AGRICULTURE, SUSTAINABILITY

Quest for Protein

30 years of searching for the soybean protein gene.

AGRICULTURE, SPECIALTY/NICHE

That New Chestnut

Bringing back the taste of Christmas.