Agriculture, Specialty/Niche September 01, 2022

A Local Cup

.

California-grown coffee pushes "drink local" to a new level.

For more than 400 years, coffee has been a global crop—grown in a narrow band in the tropics, shipped to Europe, and sold as green beans that are roasted around the world. In 2017, FRINJ Coffee turned the industry on its head, growing what may be the world’s northernmost coffee and selling a truly local cup.

"We have the ability to have the freshest coffee in the world here in California because we can harvest, process it, roast it, and get it right out the door," says Jay Ruskey, co-founder of FRINJ Coffee. Ruskey's farm near Goleta, Calif., Good Land Organics, is home to 4,000 coffee trees. It is also headquarters for FRINJ, which processes and markets coffee from 72 other small California farms.

Ruskey dipped a toe into coffee in 2002, when University of California Cooperative Extension agent Mark Gaskell gave him 40 plants to try on his exotic fruit farm. Soon, Ruskey was hooked. In 2015, he established a small nursery to sell plants to other growers, and he sold his beans as far as Japan. In 2017, he established FRINJ and launched an in-house breeding program led by another co-founder, University of California, Davis professor emeritus Juan Medrano, who sequenced the coffee genome.

Northern exposure. Ruskey figures his farm, at 34 degrees north latitude, is among the world's most distant coffee farms from the equator (another FRINJ grower farms coffee north of him). Though frost is a concern, he notes that there are some advantages to farming the crop outside the tropics. Cooler winters mature the crop slowly, so California coffee hangs on the plant 10 to 12 months before harvest. That’s about twice as long as most tropical beans. Slow maturation and 14-to-15-hour summer days enhance flavor components in the beans as well as sugars in the cherry-like fruit that help drive fermentation.

California also tends to be dry during the summer harvest, minimizing swelling and cracking that can damage tropical coffee.

On the flip side, coffee harvest is labor intensive, as crews hand-select ripe berries every two to three weeks. At California wages, that's expensive, so FRINJ has to be top quality to command a premium price.

"We are committed to help our farmers get out of the commodity driven market—avocados and lemons," Ruskey says. "If you stay with a commodity crop and the prices of your water and labor are going up, you'll get squeezed. So what we're doing is having a value-added crop so you can justify paying the wages to get quality employees. That’s ultimately our goal, like the wine industry."

To keep the profit in coffee and keep growers' eyes firmly on quality, FRINJ shares a substantial amount of its sales revenues with its growers, he adds.

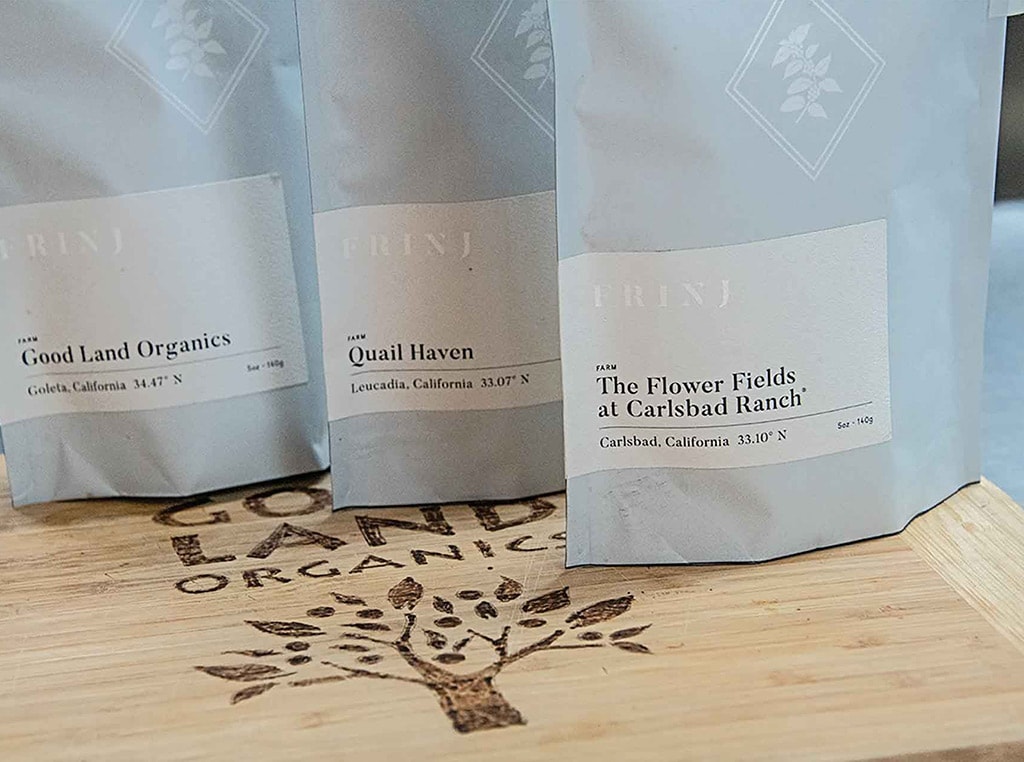

Above. Jay Ruskey planted his first coffee in 2002 near Santa Barbara, California. Ruskey is strict about brewing: 15 parts water to 1 part coffee, 205 degrees F. Roasted beans. FRINJ packaging emphasizes quality. Paige Gesualdo relies on all her senses when she roasts.

Creating premium coffee—like the Good Land Organics Caturra that was ranked 27th in the world by Coffee Review in 2014—requires more than good growing and careful harvest. There’s also a lot of art and science on the post-harvest handling side. Every step, from fermentation to drying to curing, contributes to quality and flavor.

"It's a lot like wine," says Ruskey. "You can make very nice wine grapes, but you can destroy the bottle in the post-harvest component. We’re constantly pursuing places where we can control the process. We're trying to weigh out what is important, what influences. That's the art."

Right roast. Then there's roasting, the domain of Paige Gesualdo. She's often found by the bright-red roaster, watching the temperature graph on her laptop fall, then rise, as she monitors each tiny batch of beans.

Dozens of times during the 8-to-12-minute process, Gesualdo pulls a sample of the tumbling beans. She listens for a quiet cracking as the beans dry. She checks their color and sniffs deeply, tracking as their aroma develops from hay to bread to burnt sugar and, finally, to the magical smell of roasted coffee.

Ruskey brews a carafe of Geisha, the Ethiopian cornerstone of FRINJ's breeding program. Gesualdo's light roast highlights its jasmine and sandalwood notes.

"Coffee really deserves what wine gets today," Ruskey says between sips. "We don't usually see that because we're still far removed from our coffee production. Being here in California, we now have the opportunity to show people the coffee farms, show them the processing, and have them experience what a fine coffee is really all about." ‡

Above. Gesualdo says coffee roasters are a collaborative community. Beans drop to the cooling grate. FRINJ showcases each of its participating farms. The backdrop for Ruskey's new coffee planting is the Pacific Ocean.

Read More

RURAL LIVING

Interest Blooming in the Magnolia

Millennia old trees having their moment in the sun.

SPECIALTY/NICHE

Art & the Apple

This orchard comes alive with fine art and fine apples.