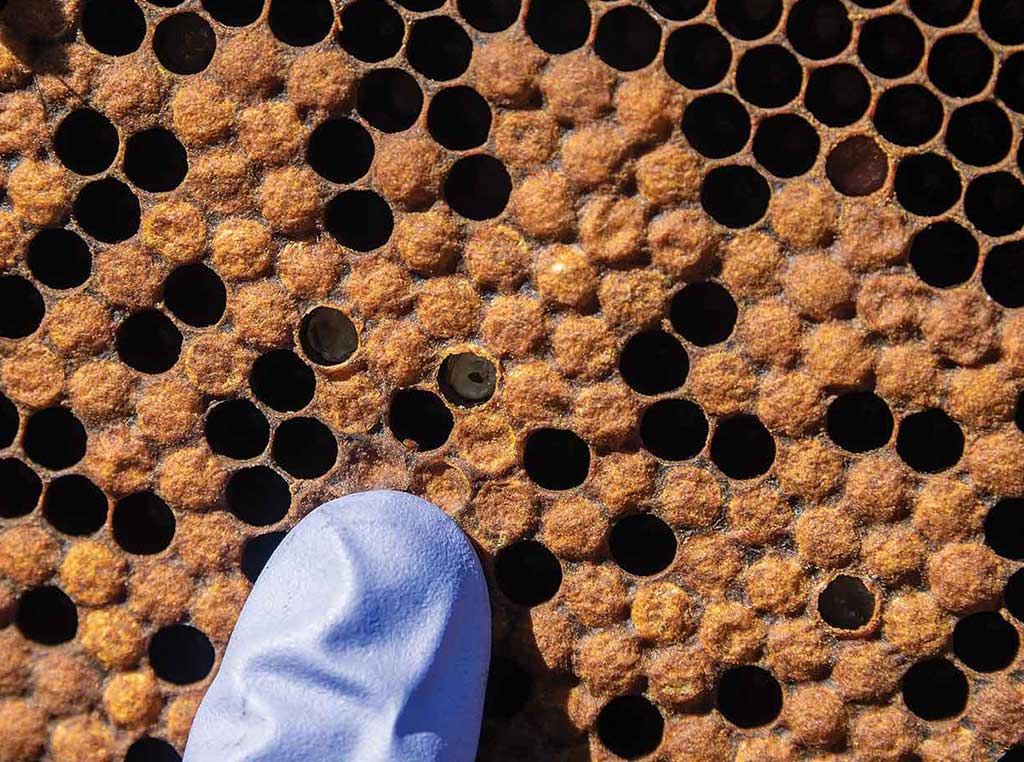

The oysters in each of these floating cages can filter up to 60,000 gallons of Chesapeake Bay water daily.

Agriculture, Specialty/Niche June 01, 2021

Aquatic Allies

Oyster farmers help tackle Chesapeake nitrogen.

A creative nutrient credit program in the Chesapeake Bay could help boost Maryland and Virginia oyster farmers and give their land-based farm counterparts some inspiration on positioning themselves as a solution to pollution.

Third-generation waterman Johnny Shockley watched one fishery after another collapse in the Chesapeake, pushing his family from wild-harvested oysters to blue crabs to pioneering Maryland’s new aquaculture industry.

Maryland changed its laws to permit oyster farming in 2009. That was one year before the states in the bay’s 64,000-square-mile watershed agreed on the Chesapeake TMDL—total maximum daily load, what the EPA called at the time a “pollution diet.” Under the agreement, annual discharges of nitrogen (N) into the watershed from all sources were capped at 185.9 million pounds. Phosphorus loading was limited to 12.5 million pounds per year, and sediment discharge cannot exceed 6.45 billion pounds in the watershed.

The fate of the two laws was soon intertwined as oysters emerged as a sink for nutrients in the bay.

A single oyster can filter the algae out of as much as 50 gallons of water per day, so a cage of 1,200 farmed oysters can filter as much as 60,000 gallons daily. Scientists determined that a 3-inch triploid oyster turns 0.13 grams of nitrogen into meat per year during its two-year production cycle. J It doesn’t sound like much, but the numbers add up.

“It’s a volume game, where you start off with a million oysters that fit in a bushel basket, and by the time they’re market size, it’s probably a couple of tractor trailer loads,” says Scott Budden, a partner in Orchard Point Oyster Co. in Stevensville, Maryland.

Credits. Last year, Orchard Point Oyster sold the world’s first oyster-generated nitrogen credits—four pounds at $400 per pound—to the Baltimore Convention Center. Johnny Shockley and his son Jordan brokered the deal through their new company, Blue Oyster Environmental. Just as his father was at the vanguard of the aquaculture revolution in the Chesapeake, Jordan Shockley is positioning Blue Oyster to lead the way in oyster-generated nutrient credits.

Municipalities and counties can take advantage of oyster credits to offset their nutrient discharges, he explains. Because they are annual credits, they will be significantly cheaper than permanent credits from mitigation bank projects like wetland restorations.

Pricing is still a question mark and so is the potential market for oyster-based phosphorus credits, Shockley says, but the credit trading sector is starting to take shape. His goal is to sell 2,000 pounds of nutrient credits this year. He also hopes to see progress on studies of bacterial denitrification in oyster reefs, which could create a permanent credit source.

Annual or perennial, oyster farmers are the heroes.

“We’re cleaning the water at very little to no cost to the taxpayer,” Budden points out. Jordan Shockley adds, “We can point to the grower and say, ‘this is where your credit comes from.’”

To Johnny Shockley, it’s all pretty poetic.

“We’ve got a protein problem we can solve, an economic problem we can solve, and we can clean the environment at the same time,” he says. “At the end of the day, it’s all about protein by way of clean water.”

Oyster farming grew 24% per year between 2012 and 2018, according to the Chesapeake Bay Foundation. Johnny (left) and Jordan Shockley broker nutrient credits. Sean Corcoran cleans bags of oysters as cages float in the background.

Read More

AGRICULTURE, SPECIALTY/NICHE

Big Bonus From Little Greens

Microgreens provide a nutritional punch and can be fun to grow.

SPECIALTY/NICHE, EDUCATION

Chilling Out

Using controlled atmosphere to fight the battle with varroa.