Agriculture, Livestock/Poultry January 01, 2026

Dairy in Context

Success is found in knowing your potential and your limits.

Story and Photos by Martha Mintz

Crossroads seem to come around at least once per generation for farm families. Those points where you have to make hard decisions. Do we get bigger or get out? Do we change our strategies or stick with what we know?

The trend for Montana dairy families for decades has been to leave the industry when they hit those crossroads. As of 2024, there are fewer than 40 licensed dairies in the state's Milk Control Program and around 8,000 cows.

The Leep family came to one such crossroads in the early 2000s. Then in their third generation of milking cattle in Montana's Gallatin County, they were feeling the squeeze from a surging population.

Even before the TV show Yellowstone made the Bozeman area popular, the population was on the rise. The county grew 15% from 2000 to 2005 and has gone on to nearly double in years since. As land value skyrocketed, farms gave way to high-end housing.

"There used to be 60 or more dairies in the Gallatin Valley when I was a kid. Now there's only five and there aren't even that many dairies in the state," says Shane Leep. Shane and his brothers Ben and Jeremy are counted in that dwindling number.

That's because when they hit the crossroads, they were willing to make big changes.

Milking 200 head at the time, the dairy wasn't big enough or profitable enough to support the number of families interested in staying. They also couldn't expand in their current location.

"We had to either quit and go our separate ways or find a spot where we could expand the dairy and commit," Shane says.

The brothers and their parents Jerry and Linda opted to pool resources and buy land 40 miles down the road in Toston.

"Our parents' willingness to put all their years of hard work on the line in order for us to have the opportunity is a big reason why expansion was possible," he says.

In the new location they were able to build their herd to 1,100 head making them the largest dairy in the state—a big fish in a very small pond, they say.

"It takes volume nowadays to be able to make money. It's a big commitment," Shane says.

The current dairy provides for three families, 10 full-time non-family employees plus a growing number of the next generation.

As their children have started to come back to the farm, the Leeps have worked to keep the dairy successful and make room.

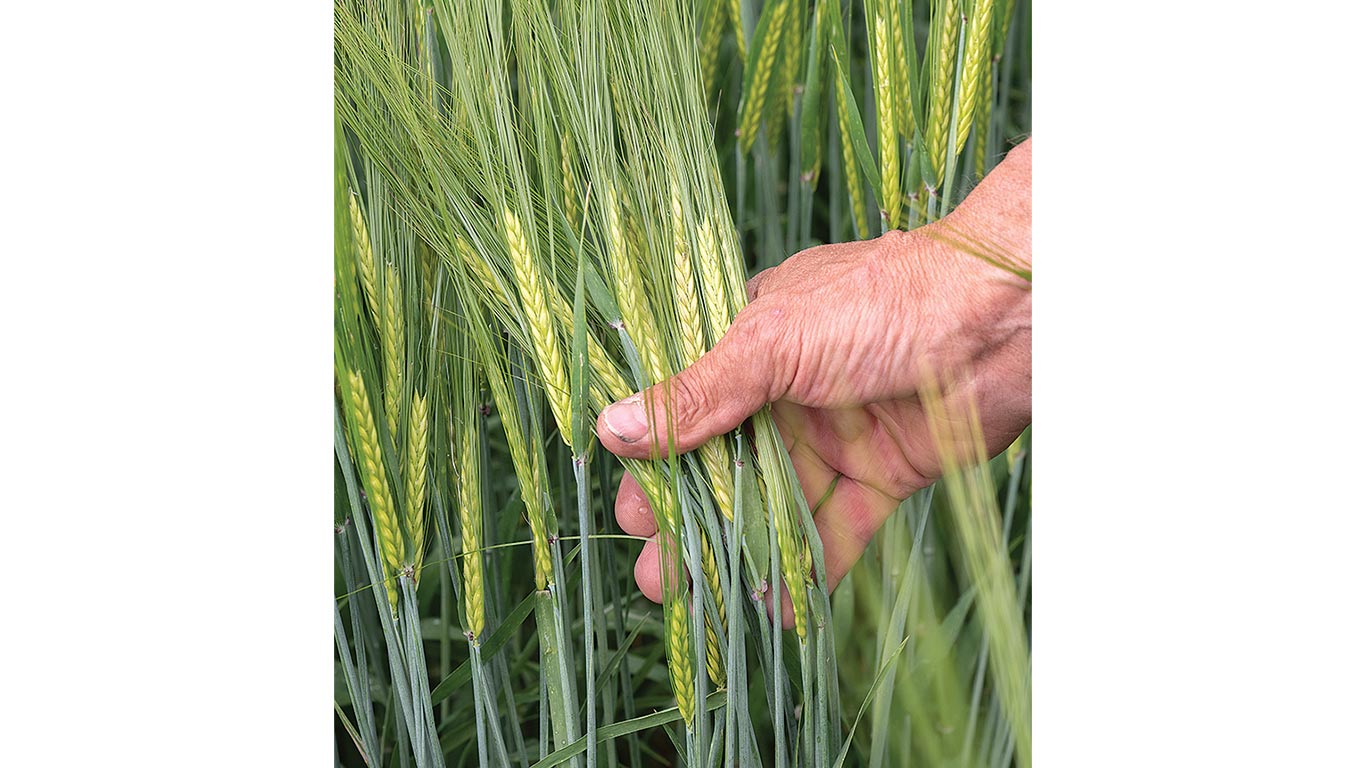

Above. Shane Leep says working within the context of the region helps earn success. Raising barley for rations instead of grain corn, for example, is more profitable. Technologies like activity trackers are doable, but not robotics.

Their philosophy is when times are good they use their gains to stabilize their business. They reinvest by updating equipment, prepaying feed and other bills, and living modestly.

"If you want a business to be successful, you have to leave the money in it," Shane says. "We've had negative margin years, but what's helped us not slide backwards is we had paid it forward in the past. That's how you survive."

Management strategies have shifted. Instead of custom harvesting their 2,000 crop acres, they invested in equipment to do more of the job themselves.

"With the next generation coming back, we have to find productive things for them to do," he says.

They've incorporated some technology. Cows wear activity trackers for health monitoring and heat detection for AI.

Using sexed semen helps manage replacement heifer numbers. Red Angus cleanup bulls maximize marketability of cull calves.

Technology has its limits. As dairies diminished, so did dairy suppliers and service providers.

"For us to put in a robotic milking facility, for example, would be a nightmare. There are no dealers, no support. We have to keep things simple," Shane says.

There are incentives for the next generation. Processors are close, keeping freight low. There's little competition for feed in the valley and room to grow.

Montana is a milk-deficit state. More milk quotas are available than people willing to produce.

"We're coming to another crossroads," Shane says. There's a good chance they'll opt to keep at it.

"The kids have potential. They're more willing to incorporate technology and they're good people managers, too." ‡

Read More

AGRICULTURE, LIVESTOCK/POULTRY

Slow Going

Slow-growing chickens are key to this company's success.

AGRICULTURE, LIVESTOCK/POULTRY

Finding Home

Idaho family creates opportunity to start their own ranch in Arkansas.