Agriculture, Farm Operation June 01, 2025

Hands-on Farming

The Karr family is digging into regenerative practices.

by Bill Spiegel

Kevin Karr remembers the exact date he and his father Jerry planted their first no-till field of grain sorghum: May 3, 1985.

"The goal has always been reducing erosion," Kevin says.

No-till dramatically reduced soil erosion on their Lyon County, Kansas, farm. Within a decade, the Karrs were 100% committed to the practice, but they still faced erosion, particularly during extreme rain events.

In 2010, a Conservation Reserve Program contract eased the anxiety of cover crop adoption and Kevin became convinced they would help lock soil in place.

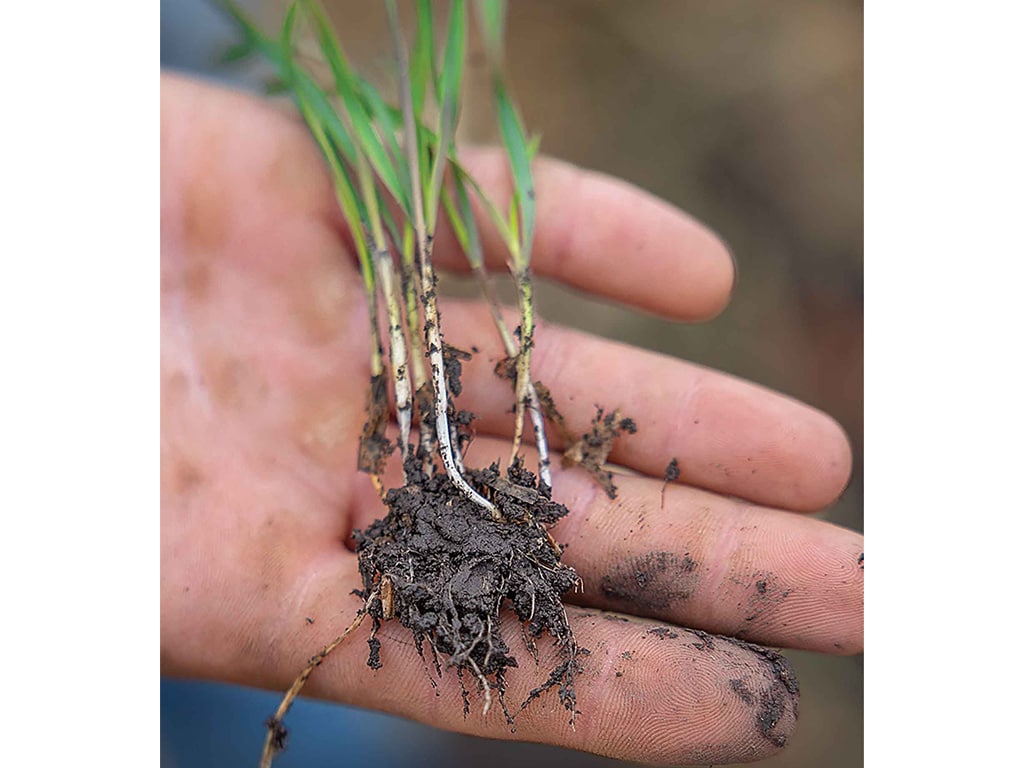

It was a steep learning curve. With his then-young son Randal by his side, the Karrs' first cover crop was cereal rye. That year they didn't get the cover crop killed until boot stage; the resulting biomass made a thick mat, which delayed planting after prolonged rain.

Now, almost every acre is planted green and most years they don't spray until after planting.

Meanwhile, they've diversified cash and cover crop rotations. Corn, soybeans, and winter wheat comprise the cash crops, with a cereal rye/brassica blend typically planted between the cash crops. After soybeans, the Karrs plant another cover crop blend, typically centered around cereal rye. They are also experimenting with barley, winter peas, hairy vetch, and oats.

Above. Cover crops after wheat harvest offer benefits like blooms for pollinators and habitat for beneficial insects, says Kevin Karr. Fall-planted cereal rye helps lock soil into place.

Summer cover. Winter wheat plays a key role in the system because the Karrs plant a diverse, multiple species blend after harvest, which is typically in late June. The interval between wheat harvest and corn planting the following spring allows for an incredible mix of plants that bring a lot of benefits to their soil.

"We focus on really building nitrogen and bringing life into the field," he explains.

The summer mix features more than 10 species, each having different benefits. Flowering plants bring in pollinators and beneficial insects, others like buckwheat make soil phosphorus more available to the next crop.

That many species also bring about root diversity, with some reaching deep into the soil and others branching out closer to the surface. All of them pump liquid carbon back into the soil. Long-term, the cover crops offer more than the immediate return of double crop soybeans after wheat, which is a popular practice in the area.

"Where we planted cover crops that grew all summer, we're seeing great benefits the following year and two years later," Kevin says.

Moreover, at least one herbicide pass is eliminated and the robust cover crop blend thwarts many problem weeds, including pigweeds and cockleburs.

Cutting costs. In the last two decades, organic matter has improved roughly 2% across the farm, he adds. Water-holding capacity has improved, and cover crops suppress weeds, reducing herbicide applications. Finally, the Karrs believe they can save money on synthetic fertilizer.

"By using cover crops, we would like to think we're going to cut back on fertilizer," Randal explains. "We're not going to need as much nitrogen, and I assume our phosphorus and potassium will be built up, too."

The Karrs also are building compost bioreactors, hoping to use compost tea in lieu of commercial fertilizer.

To many area farmers, cover crops are a tough sell. But growers can start small.

"We just started doing little pieces," Kevin says. "We're gradually getting more and more confidence that this system makes us more money and significantly reduces soil erosion compared to what we used to do." ‡