Agriculture, Specialty/Niche November 01, 2025

Winter Rhubarb?

Ontario farm's early fresh treat fills the hunger gap.

Story and Photos by Lorne McClinton

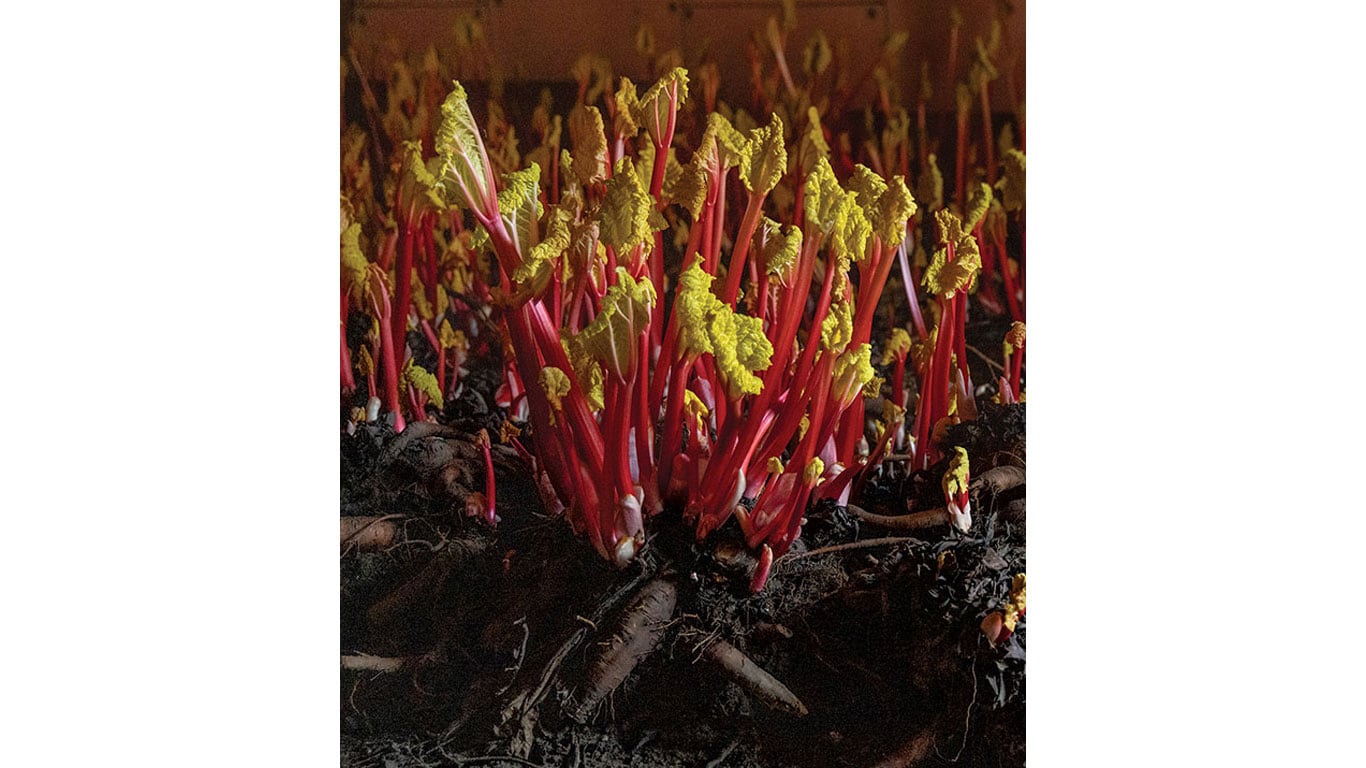

It's dark as a cave inside Brian and Jeannette French's growing sheds at Lennox Farms near Melancthon, Ontario. But our cell phone flashlights reveal a remarkable sight. The floor is covered from wall to wall with thousands of deep red winter (forced) rhubarb stalks topped with pale yellow green leaves. They're stretching upwards from their root balls searching for sunlight that never comes.

"Forced rhubarb dates back to the 1700s in France," Brian French says. "I'm not sure why, but someone thought to put some rhubarb roots in a cave during the winter and found out they would grow in the dark. It really took off, because it was a way to have something fresh to eat during a time of year when nothing else fresh was available."

French's great-grandfather brought the technique to his farm near Toronto in 1910 when he emigrated from England. The Frenches are still using scions of the rhubarb he brought with him on their farm today. By the 1940s, his grandfather was one of the largest rhubarb producers in North America.

At one time there were over 70 producers growing forced rhubarb in Ontario. However, the energy crises in the 1970s forced small producers out of the business. Their numbers have been dwindling ever since; the Frenches are the last producer in Canada still growing it. It's very popular, he can sell as much as he can produce.

Above. Dawn Woodward says she embraced forced rhubarb because it provides a local, fresh, and springy ingredient early in the season. She loves the beautiful red color and that it can be used in either sweet or savory dishes. Forced rhubarb is grown in complete darkness. Since no photosynthesis occurs it has the rhubarb flavor without the tartness and stringiness. Brian French's family has grown it since 1910.

Barely changed. Their process has barely changed over the past 115 years. They start their plants out in their fields and leave them untouched for two years. After that, they'll harvest 20,000 roots and move them into one of their five Quonset-style growing sheds. There they are kept in complete darkness and at 5° C to place the plants in a cool dormant stage for at least 40 days. Starting in mid-January, temperatures are raised one shed at a time to 13° C with propane space heaters. The increase convinces the plants that spring has arrived and the roots send out fresh stalks.

"They're grown in complete darkness," French says. "It's the same process people have seen when an onion they've stored in a cupboard sends out a shoot. We only turn the lights on to water them and to harvest them every five days. There's no photosynthesis happening so the plant can't move oxalic acid out of the roots into the leaves. So, you still have that nice rhubarb flavor, but without all that tartness and stringiness that field rhubarb has. It's just a totally different product, a real delicacy."

All the energy the rhubarb needs to produce stalks comes from what the plants stored in their roots during the two years they grew in the fields. The roots are firm and bursting with energy when they go in and then exhaust it all in six weeks of production. They're just fit for compost by the time their season wraps up in May.

Their production is sold directly to bakers, chocolatiers, beer and cider makers, and in specialty stores throughout the Toronto area through the late winter and early spring. Dawn Woodward, owner of Evelyn's Crackers & Wholegrain Bakery in Toronto's trendy Liberty Village neighborhood, is an avid customer.

"I'd heard about forced rhubarb from Instagram friends in the UK," Woodward says. "All the British cookbooks talk about it. The timing for Brian's rhubarb is fabulous. It comes in the spring hunger gap when we're desperate for something that's fresh and springy, but the local farms won't have much available until the end of June."

Woodward says she likes baking with forced rhubarb because it has a more delicate taste than field rhubarb. Unlike field rhubarb, it isn't too sour to eat raw. Plus, because it's not fibrous, it cooks very quickly.

"Rhubarb is a vegetable, and it does have a slight vegetable taste," Woodward says. This rhubarb can go either sweet or savory; you can make pies, you can make chutney, you can use it to make a nice pork dish, or you can put it in a salad instead of celery. Put in a little citrus and some sugar in there and suddenly it's this really delicious tart. It's just a great local ingredient." ‡

Read More

AGRICULTURE, SPECIALTY/NICHE

Farm Naked

Naked barley is gaining ground…and fans.

AGRICULTURE, EDUCATION

Phytoculture Replication

Canada farmer takes a high-tech path to farming.