Agriculture, Education November 01, 2025

Solving Sawfly

Farmers are eager for tools to beat the pest.

Story by Bill Spiegel, Photos by Lorne McClinton

Cary Wickstrum needs winter wheat.

It is the foundation for a crop rotation that includes millet and dryland crop rotation in northeast Colorado. But like many farmers in the region, Wickstrum fights wheat stem sawfly, a pest that causes tremendous lodging damage in winter wheat.

Wickstrum, who farms near Orchard, Colorado, reckons when infestations are bad, yields plummet by 50 to 60 percent. Adding insult to injury is the impact on the next crop in the rotation. Wheat stubble provides soil armor that helps prevent wind and water erosion and captures snow.

As wheat stem sawfly infestations have gotten progressively worse the last 15 years or so, area farmers tried different strategies: larger fields, more crop rotation, and haying field edges. At best, these approaches had mixed success.

"It got to the point where conventional varieties were flat on the ground. It was pretty devastating," he says.

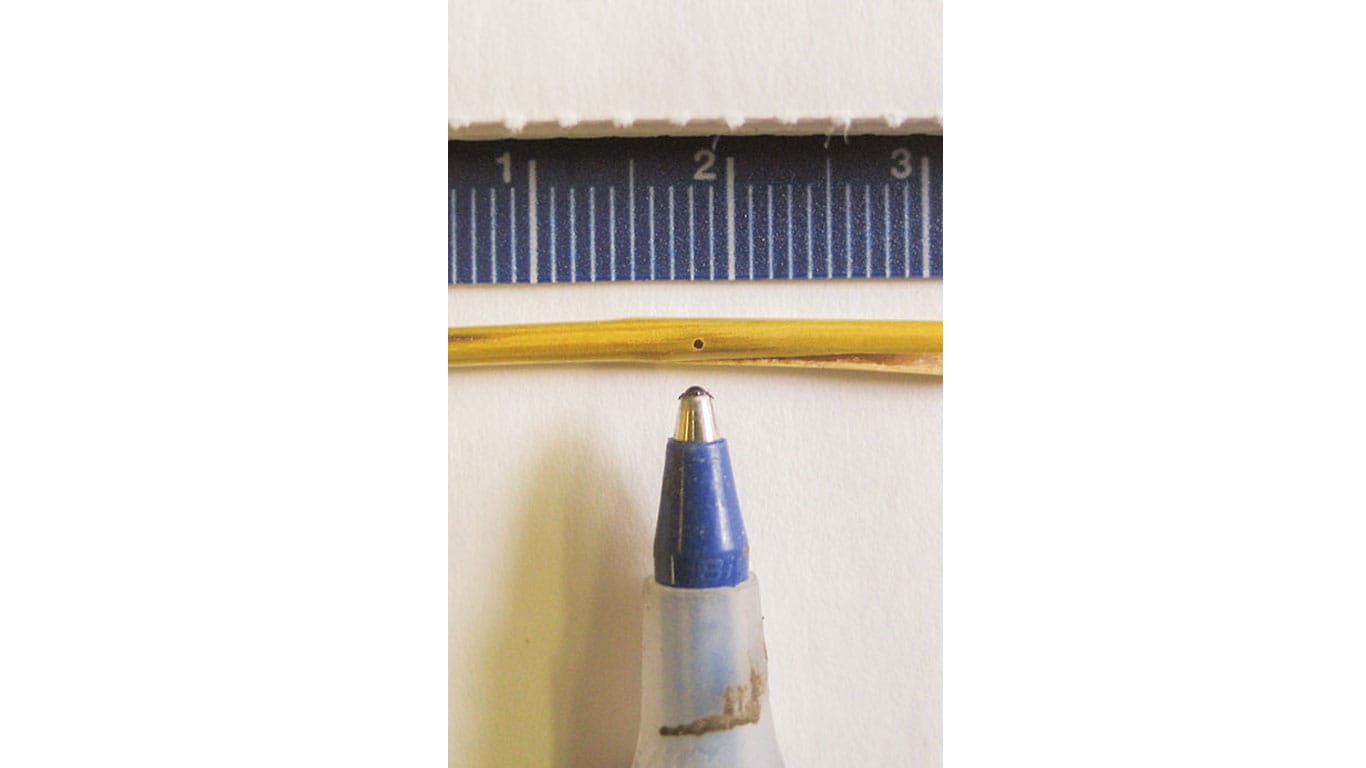

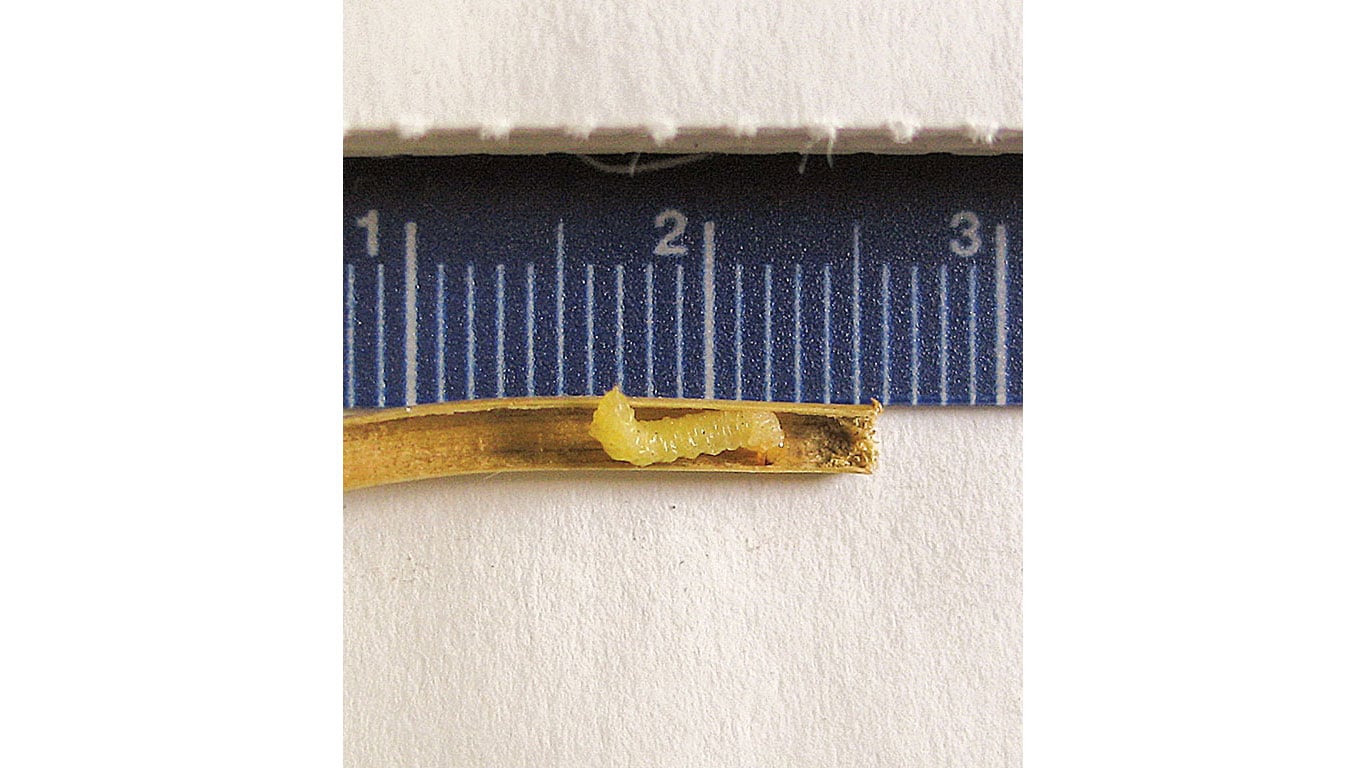

The wheat stem sawfly is a wasp, about three-quarters of an inch long and emerging in late May and active when winds are calm and temperatures are above 50 degrees. Females deliver eggs inside hollow-stemmed, grassy plants and as larvae mature, they tunnel into the bottom of the plant, weakening the stem and causing lodging. Although females only live about six weeks, there are multiple generations of sawflies each season.

Above. Wheat stem sawfly females tunnel inside wheat plants to lay eggs. Larvae tunnel down the plant and eventually cut through the perimeter, causing lodging. The pest causes millions of dollars in lost yield each year.

Moving south. Northern state wheat growers have battled wheat stem sawfly for years, but the pest has migrated south. Now, it can be found in the western third of Nebraska and a few counties in northern Kansas, says Brad Erker, executive director of Colorado Wheat, a grower advocacy organization.

Pesticides are not feasible, because there are multiple generations of sawflies each spring, each of which would require a separate application.

Land-grant universities and USDA researchers are teaming up to fight the pest, Erker says.

Wheat breeders at Colorado State University (CSU) quickly developed semi-solid stem varieties of wheat; the pith inside the stem helps reduce lodging.

The first generation of these varieties have some yield drag compared to Colorado's best hollow stem varieties, but they are a temporary solution to the problem.

The next generation of semi-hollow stem varieties from CSU possess even better yield potential and agronomic traits, and could eventually possess the herbicide-resistant traits Colorado farmers need.

At Nebraska's High Plains Ag Lab, specialists believe Bracon spp., a parasitoid wasp and natural predator of the wheat stem sawfly, is effective in reducing the pest. In 2025 researchers began work on a project in which the Bracon spp. wasps are baled in straw and transported to affected acreages where the bales are unrolled and wasps are left to do their work. The next phase of research is to see if the predators will survive and multiply from one year to the next, Erker says.

Federal funding. USDA's Agricultural Research Service has invested in the Wheat Resilience Initiative, which studies potential new varieties for their ability to withstand wheat stem sawfly and other wheat pests and diseases. And finally, scientists at the Wheat Genetics Resource Center in Manhattan, Kansas, are screening wild relatives of wheat for their ability to resist the pest.

The last two initiatives are long-term research; discoveries found in them will take years to incorporate into varieties farmers can use.

Meanwhile, farmers lose about $30 million each year to yield loss, according to CSU studies. With wheat being a primary option for farmers in this area, finding solutions is imperative. "We don't have a lot of other options in our rotation other than wheat," Wickstrum explains. "It is the most viable option for us. "We're in such an arid area and we need residue. Wheat is our mainstay." ‡

Read More

AGRICULTURE, FARM OPERATION

Crunching the Numbers

Peanut farmers crack code on adding value through artisan butter.

AGRICULTURE, SPECIALTY/NICHE

A Bit of Zest

Underground greenhouse keeps prairie life fresh.