Agriculture, Farm Operation September 01, 2025

A Lesson in Resilience

A Kansas farm endures despite life-altering tragedy.

by Bill Spiegel

When Jen Campbell began giving her husband chest compressions, she didn't know how long it would take to revive him.

She pressed hard on his chest and counted: One. Two. Three. All the way to 30, then two breaths into his mouth. Over and over, for 15 straight minutes.

She yelled at Matt, who lay motionless. She yelled at the sky, cried, and yelled some more.

As she performed cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) on Matt, she thought "it can't end like this." He was the father of their three children; her business partner. The yin to her yang. The leader of "The Campbell Scramble."

The date was June 30, 2023. Jen had spent all day working in flower beds at Woolly Bee Farm, the 10-acre property she and Matt bought in 2016. Matt had just gotten home from work and they each carried a beer as they chatted and walked through the gardens. The sky was clear, although storms were expected later.

Suddenly, everything changed. Jen says it was like in the movies when the actor gets up from the ground, their mind in a fog and unable to hear.

This, however, was real life.

She looked over to Matt, sprawled motionless on the ground, and knew he had been struck by lightning. She crawled to him and the CPR training she learned at a Red Cross class years ago suddenly kicked in.

Not many spouses could do what she did for 15 minutes. In emergency rooms, CPR is performed for one minute before the next person takes over.

Some people can't do CPR when they hear cartilage cracking or bones breaking. The lightning strike took her hearing away briefly; if she could have heard how badly she hurt her husband, could she still have done it?

She doesn't know.

She learned several weeks later that four of his ribs were broken.

Just like that, a new chapter at Woolly Bee Farm began.

The aftermath. Each year, lightning strikes kill roughly 20 people in the U.S. and injure hundreds more. Some, like Matt, suffer permanent brain injuries. He spent 11 months in hospitals and therapy centers in Topeka, Kansas City, and Chicago.

Jen made countless trips between the hospital and the farm, trying to provide some stability for the couple's kids: Cade, now 12; June, 10; and Clare, 6.

Matt finally came home in May 2024, and returned to his job as a mechanical engineer at Kansas State University. The accident compromised his cognitive and physical abilities.

"I'm generally a happy person, but I will never be back to 100%, which is frustrating," he says.

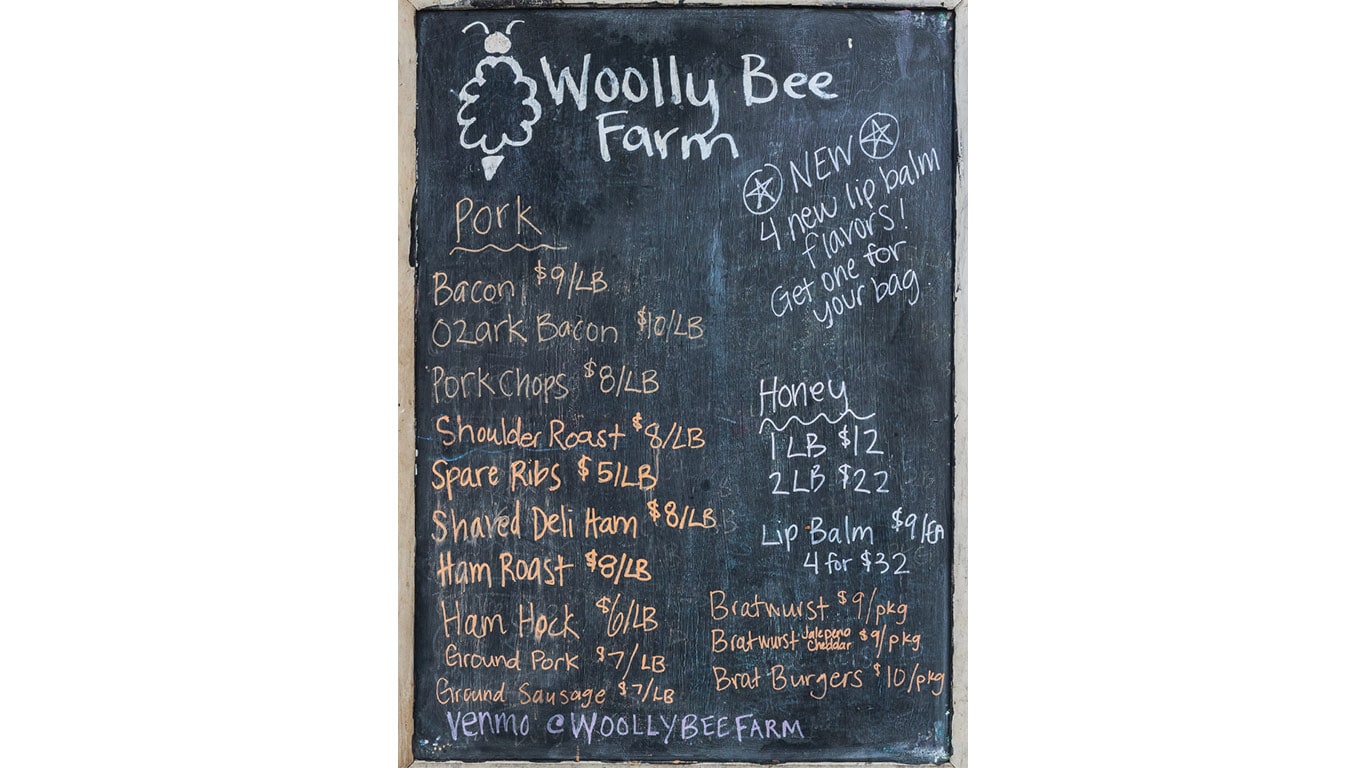

Above. Jen transplants larkspur in one of her gardens. The Campbell family: Clare, Jen, Cade, Matt and June. Snapdragons, one of the hundreds of species of flowers at Woolly Bee Farms, get their start in the Campbells' greenhouse. The farm sells thousands of cut flowers to markets in eastern Kansas and Kansas City. Pork, poultry, and honey are farmers' market staples; in-season, berries and cut flowers are also best sellers. When Woolly Bee began selling cut flowers, the Campbells threw themselves into research; this is an arrangement of snapdragons, Bells of Ireland, ranunculus, stock, alliums and lilies. At the Manhattan Farmer's Market, customers rave about their honey products. The swine herd features Iowa Pasture Pigs. Free-range chickens, including this rooster named Galaxy, thrive at Woolly Bee Farm. Poultry are processed at a USDA-inspected meat bird facility in Garnett, Kansas; swine are butchered at a plant in Clay Center, Kansas.

Dreaming together. Matt and Jen were each captains of the men's and women's soccer clubs at Kansas State University when they met.

Immediately, there was a connection; they soon became inseparable. Not long after their wedding, Matt reserved a plot at the Community Garden, despite neither of them having any experience with gardening or farming.

They were proud to share homegrown food with friends and neighbors and began to dream bigger. "We kind of thought, 'Hey. What if we did this on a larger scale?'" Jen recalls.

"We believed in ourselves," Matt adds. "It's the best thing, working with my wife and growing food for family and friends."

In 2015, they found a house and 10 acres of land near Wamego. The property had a high tunnel, livestock fence, an old orchard, and some raspberry plants.

It needed work, but the Campbells saw its potential and dove in: they raised sheep, honeybees, berries, Swiss chard, and lettuce. Friends and family were their first paying customers.

"It took a few years while we figured out our vibe," Jen says.

They decided to add cut flowers, and Jen relished that challenge. She took online flower farming courses and bought tons of books. Matt devoted hours to research as they planned and dreamed.

Jen learned that pigs do a great job of clearing woods, so they bought piglets to root through an old orchard.

When Matt was at work, Jen devoted hours to plants and animals. When he came home, they worked until well after dark.

"We joked that we were living two lifetimes in one, because we were always going," Jen says.

The Campbells built strawberry beds and added chickens; made dozens of beds for cut flowers and built a greenhouse to start plants. Eventually, they began selling their products at the Manhattan Farmer's Market. The cut flower business boomed; they sold hundreds of thousands of them in the area.

Jen loved planting, caring for, and harvesting crops of food and beauty; Matt took care of all the maintenance and repairs, thriving on the challenge. One day, he pulled into their driveway behind the wheel of an ancient tractor he bought at an auction a couple miles away. The grin on his face was epic, Jen recalls.

Their goal was for Matt to retire early and for the farm to be their source of income.

During the day, they texted constantly, sharing ideas and making to-do lists.

"We got stuff done all the time," she adds. "We were a great team."

And then, the accident.

In a small town, word travels fast. A GoFundMe campaign generated more than $100,000 in donations. Dozens of people volunteered to help at the farm while Jen was with Matt during hospital and rehab stays. Friends and strangers bought gift cards or prepared meals for Jen's family, says her sister Lindsay, who—despite having a full-time job of her own—became the de-facto farmer, supervisor, and farmers' market clerk during Matt's hospital stays.

If Jen couldn't be with Matt, another family member stayed with him. Helpers divvied up farm chores, sold farm produce, and provided as normal a life for their children as possible. The army of supporters was humbling.

Matt is improving. With traumatic brain injuries, recovery is slow; the results can be frustrating. He had to relearn so much. Doctors feared he would never recover. "And here I am, walking and talking," he says.

When they bought the place, the Campbells had an arrangement. Jen would pour love into the animals, while Matt would do the hard things, like castrating the pigs and taking animals to the locker plant. Those chores now belong to her.

Keeping the farm going, ensuring Matt's therapy progresses and getting the children to school and activities is not easy, but Jen is not one to sit still. While her kids were at soccer practice last fall, instead of watching them play, she explored nearby woods, pulling a kids' wagon and hunting for acorns to feed the pigs.

"It was like, 'don't mind me. I'm just a parent picking up acorns,'" she laughs.

The new normal. On any given Saturday morning, her farmers' market spot is packed, but it's not the same.

"It's not as fun without Matt," she says. "I still enjoy it, but I feel like something's missing."

She has co-hosted several CPR awareness events in Matt's honor.

"I can't fix Matt, but I can fix people not knowing how to give CPR," she says.

Certainly, not every story has a happy ending. Working mostly alone while her partner recovers, Jen has her share of dark days.

"Some days the grief is as large as an elephant and I drag it around," she says. "Sometimes it's more like a mouse I stick in my pocket and carry with me."

But she relishes the victories: Visiting with customers at the farmers' market. Having her kids close. Working outdoors.

"What person who's grieving and going through a bunch of stuff is like, 'oh please. Let me go sit at my desk job,'" she says. "I get to grow beautiful things, and rage on stuff for a little bit."

Neither she nor her loved ones can imagine Jen doing anything else. She has become a farmer, her sister Lindsay says.

Nikki Bowman, a beekeeper near Riley, Kansas, harvests Woolly Bee's honey. Her friend Jen is incredibly tough, she says.

"She lost her business partner, the go-to person she could count on as an equal," Bowman explains. "She just somehow poked through all that, kept going and is now carrying even more."

There is some solace in her profession.

"I like growing a product that spreads joy to people," she says. "There is a lot of beauty here. And life is hard, but maybe that makes it more worth it." ‡

Read More

AGRICULTURE, SPECIALTY/NICHE

Heating Up Summer's End

Pueblo chile farmers roast up spicy delights.

RURAL LIVING, EDUCATION

Going Bats!

Among nature's most misunderstood creatures.