Agriculture, Specialty/Niche September 01, 2025

Backyard Biochar

Pyrolyzed wood waste can jump-start garden soils.

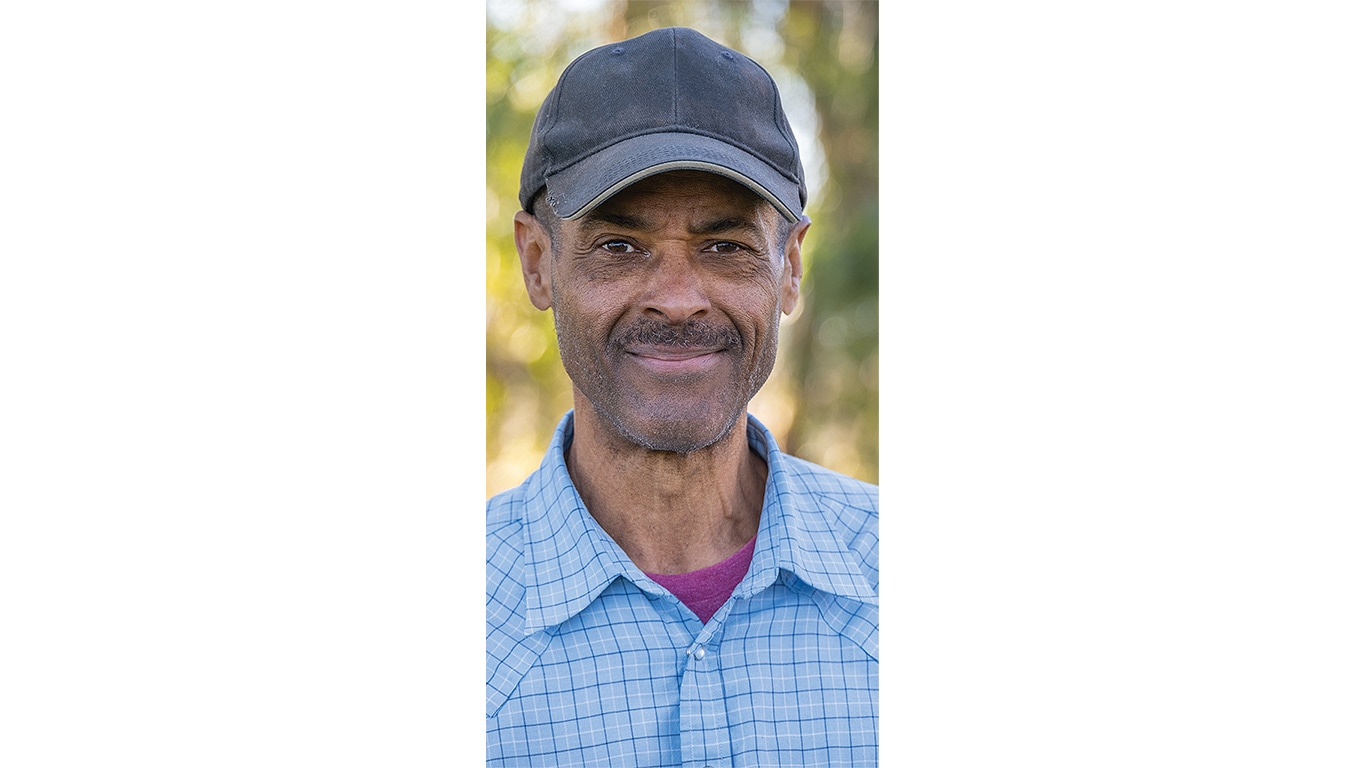

by Bill Spiegel, photos by Steve Werblow

One of the newest trends in garden and farm soil amendments is thousands of years old.

Biochar—charcoal that gardeners and farmers crush and add to the soil—converts cellulose-laden waste biomass like tree branches and logs, lumber waste, crop residues, and yard waste, into a carbon-rich soil supplement.

Eric Johnson, a regenerative farmer near Chico, California, is a big believer in biochar. He and his wife Rebecca collect tree deadfall and prunings throughout the year to make biochar on their 40-acre property.

"Rather than taking all of the material I collect every year and burning it and having it go to waste, I put that valuable resource back into the soil," he says.

The result? Bits of carbon that boost water and nutrient retention, promote healthy microbial activity, and improve soil health.

The wood waste used to make biochar is called feedstock, and it is "cooked" in a kiln, via pyrolysis, or lack of oxygen.

"During pyrolysis, organic materials like carbon, nitrogen, hydrogen, and oxygen within the feedstock decompose into solid, liquid, and gas products. The inorganics remain solid and become concentrated in the biochar," says Akio Enders, research manager in the Soil Health Lab at Cornell University.

The pyrolysis process emits "off gas" from the feedstock, which fuels the fire until it either dies out or is quenched with water. After pyrolysis, the former feedstock is light, porous and if wood, 90% carbon (crop stover or seed hulls may contain about 70% carbon).

But it's not biochar yet. That happens when users "charge" it with nutrients or inoculate it with microbes before adding it to soil. And that is a critical step, says Dan Hettinger, founder of Living Web Farms Biochar.

A gram of biochar has roughly 300 square meters of surface area, providing a lot of space for microbes and water to gather. If users don't charge the stuff with nutrients and inoculate it with microbes, biochar acts like a sponge, taking in nutrients, moisture, and microbes from the soil.

"Biochar is adsorptive, so if applied raw it will "suck in" nutrients," Hettinger says.

When charged and inoculated, nutrients and microbes reside in those nooks and crannies of the biochar particles. Plant roots and soils benefit from that healthy community of minerals and microbial life by increasing nutrient and water availability.

Biochar has a negative charge, so it will attract positive-charged elements like magnesium and calcium, he adds.

Above. Johnson and his wife Rebecca have several biochar videos on their YouTube channel, Porterhouse and Teal. One biochar method uses a 30-gallon barrel inside a 55-gallon drum. Burning wood in the outer drum produces offgas, the heatsource to fuel inner barrel pyrolysis. Chickens "charge" the biochar with their waste. California farmer Eric Johnson makes biochar for his 40-acre regenerative homestead. Biochar adds carbon, plus improves water- and nutrient-holding capacity in his garden beds.

How to make it. In her book, "The Biochar Handbook," Kelpie Wilson describes various ways to make biochar, all of which perform pyrolysis to a degree: the retort, the flame-cap kiln, and the conservation burn. There are myriad variations on each of these methods; you can search on Johnson's YouTube channel, Porterhouse and Teal, for step-by-step instructions on how he makes biochar using two of them: the double-barrel retort, and the flame-cap kiln, which uses a trench to hold feedstock.

"They both have their benefits and might be used in specific applications. The retort is a closed system, so you'll be able to exclude oxygen in a more efficient manner," Johnson explains.

The downside of a closed retort, however, is the amount of material you can put inside. A 30-gallon barrel full of feedstock will reduce to about 40% after pyrolysis; processing the raw biochar reduces the yield even more.

He lets pigs and cattle crush the biochar, and their waste adds nutrients to the mix. Then, Johnson spreads that mix onto piles of compost on which chickens get free reign to roam. The result is a nutrient-packed and carbon-rich amendment.

"I don't have to do the work of charging and inoculating if the animals are doing it for me," he explains.

After several months in compost, inoculated biochar is added to soil in garden boxes and around trees or other perennials at a rate of about 3 to 6 cubic feet of biochar per 100 square feet of soil.

Users can topdress fields with biochar, although soil incorporation is recommended.

Soil boost. Users will typically see quicker results when biochar is added to coarse or medium-textured soils, according to Michigan State University findings. But it is a long-term effect on all soils. In the Brazilian rainforest, Terra Preta soils supplemented with biochar nearly 2,000 years ago are still dark, rich, and productive, while nearby non-treated soils are weathered, eroded, and unproductive.

Johnson is aiming for similar benefits.

"I know what I'm putting in the soil is going to be there long after all of us," he says. "It's going to have some benefit to soil, no matter how large or small by improving the tilth, water retention, and providing microbial habitat." ‡

Read More

AGRICULTURE, FARM OPERATION

Strength in Numbers

Working together keeps seven-gen farm family ticking.

AGRICULTURE, EDUCATION

Greener Rice

Ecological and economic sustainability make a big impact on small fields.