Agriculture, Farm Operation December 01, 2025

The Woven Path

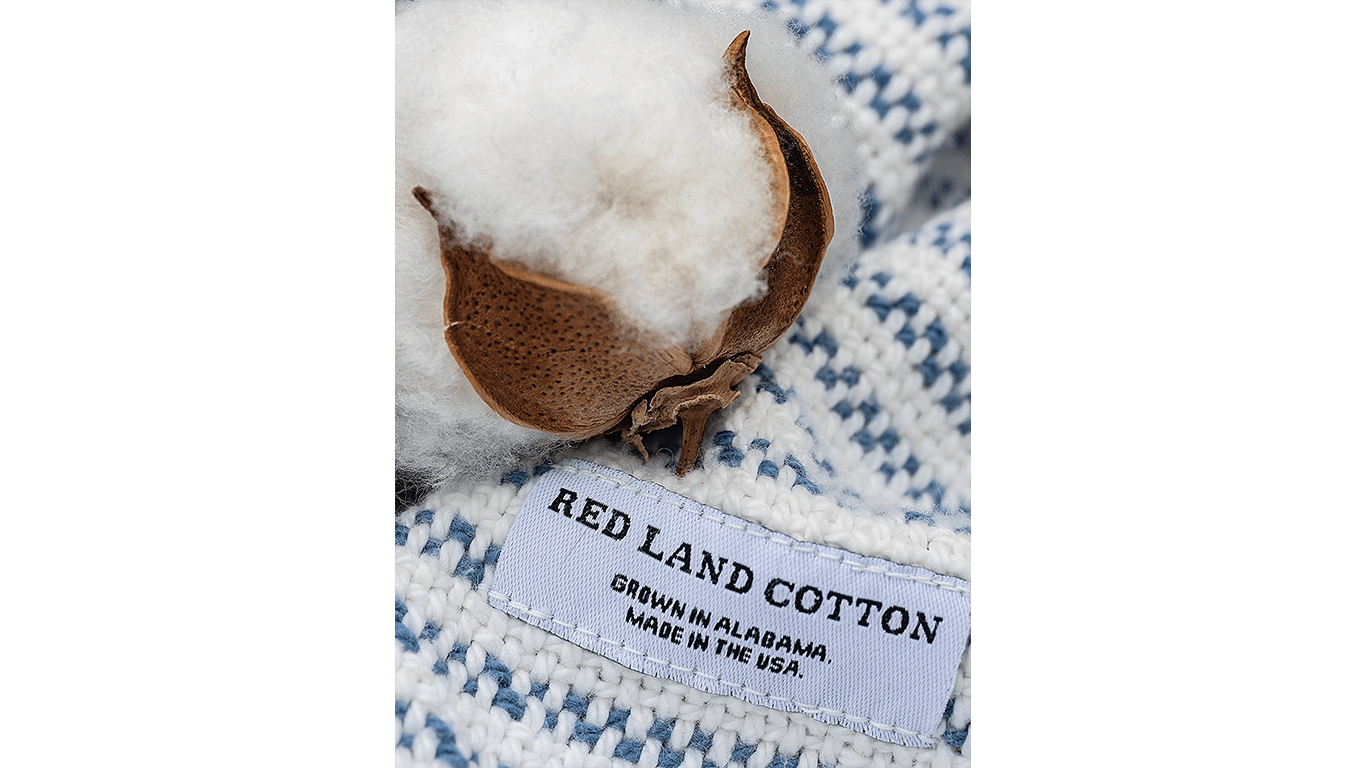

Cotton farmers take fiber from field to function.

Story and Photos by Martha Mintz

Mark Yeager sneaks a peek at his phone with a grin. He was quick, but not fast enough to avoid being called out by his wife Cassandra and kids, Joe, Anna Brakefield, and Mark Jr. from their seats around the table.

"He sets his alarm so he can check that app every 30 minutes all night," Joe goads.

It isn't social media or the weather bringing him such delight, it's an app tracking online orders for their family's Red Land Cotton linens business.

The numbers are evidence of a realized dream and a decade of work. Sheets, blankets, towels and other textiles made in the United States from cotton grown on the family's North Alabama farm are headed out to more happy customers.

The journey from commodity price taker to value-added product price-maker started in 1994 when the Yeagers built their own cotton gin.

"I wanted control of processing and marketing, and to collect more of the profits being made on my crop," Mark says.

In 2015, the family took the next step with Red Land Cotton, producing textiles for direct sale to consumers.

"I could buy a pair of pants for $40 that only took a couple pounds of cotton to make. I was getting maybe $.70 per pound for the cotton," Mark says. The realization inspired him to enter the textile industry. "After 10 years, I now know a lot more goes into making and marketing a textile than just cotton."

The family navigated the process of finding U.S. businesses to spin bales of lint into yarn, weave fabric, and cut and sew the sheets into bedding. Simple sheet sets provided a straightforward entry to the market.

"Our first order was 50 bales of cotton that made 20,000 yards of fabric," says Anna, who manages marketing and operations for Red Land Cotton. At 7 yards per sheet, that run made 3,000 sheet sets. "It was a big investment for us, but small potatoes for the processors."

Anna was a graphic designer before returning to help make Red Land Cotton a reality.

"I knew nothing, but the internet is an amazing tool," she says. While her brothers focused on farming, Anna, Mark and Cassandra worked on growing the textile business. In 2024, they made 350,000 yards of fabric just for sheets. They have expanded to include more linen options, and are venturing into more prints and colors.

The supply chain has presented significant challenges. The biggest bottleneck was the cut-and-sew process. To remedy the situation, they leased and restarted an abandoned Mississippi cut-and-sew facility.

"There's a rich history of textile manufacturing in the area," Anna says. There was equipment and a community of skilled sewers. They also used a local Moulton, Alabama, cut-and-sew business. They've since purchased the business and brought it into their warehouse and store facility.

Above. When the market for organic cotton didn't materialize, Gary Oldham went the value-added route making simple organic t-shirts and eventually other apparel with his crop. Cotton lint leaves the farm in bales and returns to be cut and sewed into various linens sold through Red Land Cotton. Navigating the textile industry, including through Covid, has been a challenge. (Back Row) Joe, Mark Jr. and Mark Yeager (Front) Anna Brakefield and Cassandra Yeager take cotton from field to textiles.

Organic tee. About 700 miles to the east, Texas Panhandle cotton farmer, Gary Oldham, also found himself frustrated with cotton market instability.

Oldham left a career in aerospace engineering to help his mother on the farm after she had some serious health issues.

In 1992, he was transitioning alfalfa fields back to cotton when he was encouraged by the Texas Department of Agriculture to go organic. They'd recently started an organic certification program and premium markets were anticipated.

"It turned out there wasn't an established market for organic cotton," Oldham says. He set out to make his own, quickly finding a potential deal to supply organic cotton t-shirts for the 1994 winter Olympics. The deal fell through, but Oldham sees it as a blessing and a kick.

"If I would have started with a contract that big before I tackled manufacturing problems and learning the process, there's no telling what would have happened," he says.

Instead, Oldham gradually built a thriving business around basic organic cotton t-shirts using cotton he raised.

"The market for raw organic cotton has developed throughout the years, but it's still up and down. I wanted a more stable market," he says.

A bale of cotton makes around 1,000 t-shirts, he says. The farmer gets around $.60 per pound on the open market. A basic retail t-shirt selling for $14 translates to $28 per pound for the same cotton.

Oldham puts costs of production at 30% of the t-shirt's value, leaving a healthy profit margin while maintaining a conservative price point.

"Farmers typically grow a crop and beg someone to buy it," he says, noting some in the area are even moving away from cotton. "I'm able to match production with my market so I'm never in a position where I have to give my crop away."

To market. Each farm has taken control of the production process, but they take different approaches to marketing.

Red Land Cotton makes the majority of their sales direct to consumers using digital marketing and a farm store front.

"In retail, diversification in marketing is as important as diversifying crops in the field," Anna says. They sell through multiple online channels. "We want to have a presence anywhere people shop."

Oldham is 50/50 retail and wholesale with his business, SOS From Texas.

"There are bigger profit margins in retail, but there are also more issues and logistics to deal with," he says. He's happy to sell wholesale lots to others who customize and resell.

Both Red Land Cotton and SOS From Texas take pride in their cotton, that they're 100% made in the U.S.A., and that they provide jobs. During the pandemic, Oldham's orders helped keep some of his supply chain partners in business when other income streams dried up. The Yeagers had similar stories to share.

"We could automate some of our processes, but all the hands that touch our product from the farm to sewing is part of our story. We're employing friends and neighbors across the nation," Cassandra says.

Both families use their platforms to educate consumers about farming and the fiber industry and enjoy the off-farm connections they make as they navigate their businesses. ‡

Read More

AGRICULTURE, SPECIALTY/NICHE

Boughs That Bind

Christmas tree farming connects land, family, and tradition.