Agriculture, Farm Operation December 01, 2025

Hiding Place

Old-school tanning techniques.

Story and Photos by Steve Werblow

More than 5,000 years ago, a traveler died on a mountain that is now the border between Austria and Italy, wearing a sheepskin coat, goatskin leggings, a bearskin cap, and cowhide shoelaces. When his mummified body was discovered by hikers in 1991, it illustrated how ancient people have used animal hides since prehistoric times.

Tanning technology has taken many turns over the millennia. Early preservation methods to keep pelts from rotting evolved into sophisticated techniques using brains and other emulsified fats to preserve skins. Later generations harnessed natural tannins from tree bark. In the 1850s, tanners learned to replace plant tannins with chromium-based chemical compounds, a cheaper, industrial approach that put most other processes out of business.

But over the past few decades, a growing number of leather enthusiasts have rediscovered and revived classic techniques and made natural home tanning viable.

"It's very tactile, it's very physical, and I love the transformation that's involved," says Matt Richards, an Oregon homesteader and tanner who teaches bark tanning classes on Zoom. His meticulously researched how-to book, Deerskins Into Buckskins, has become a brain tanner's bible, with hundreds of thousands of copies sold worldwide since he first published it in 1997.

By the time he wrote his book, Richards had already traveled worldwide to learn and teach about tanning, and launched a homestead tannery, Traditional Tanners, with his wife Michelle.

Above. Matt Richards prepares to load a hide into a fleshing machine. Tanoak is a softwood forester's trash and a tanner's treasure; the West Coast once had a booming industry supplying bark to tanneries. Ground bark is steeped like sun tea to draw out the tannins to process hides. Bark cures in the Oregon air.

Beautiful. "You start with this thing that's raw and often kind of gross, and through working with your hands and the process, you've turned it into something completely different and super-durable and beautiful by the end," Richards explains. "I've found that very satisfying. We only tan hides that would otherwise be going to waste and we use natural techniques, so it's a model that's more friendly to the community and the environment."

That philosophy is captured in the moose hide on Matt and Michelle Richards' couch. Michelle saw a truck hit the moose on a highway. She put the moose out of its misery, called Matt to bring it home and tan it, and its legacy lives on in a gorgeous tanned hide. The stunning spotted pattern of an Axis deer drapes a chair, while luxurious sheepskins make the living room feel like a cozy nest.

In Michelle's design studio, there's a photo of actor Jason Momoa wearing one of the Richards' famous buffalo robes, a mainstay of their tanning business. Another image shows Alden Ehrenreich as Han Solo, wrapped in a coat crafted by studio costumers from buffalo hides supplied by the Richardses. There's the hide of a rattlesnake from the front porch, a tanned salmon skin, and a massive selection of leathers and hair-on hides in a rainbow of naturally dyed colors and range of textures. Michelle's coats, throws, handbags, and other creations demonstrate the nearly unlimited possibilities of leather, hair, and fur.

Flexible. Tanning is the process of turning a moist skin—which will rot just like the rest of an animal carcass—into a dry, durable, flexible fabric that can last for decades of heavy use.

The miracle of skin is an extremely strong network of interlocked, twisted fibers made of a protein called collagen. They are lubricated and nourished by a mucus substrate of water, oils, and proteins, including the hyaluronic acid that cosmetic companies advertise so enthusiastically.

Making leather starts with removing flesh, fat, and membranes to isolate the skin. A chemical bath—originally a strong alkaline solution made from wood ash or mineral lime—allows tanners to remove hair from the surface and mucus from inside the skin.

The tanning step coats each fiber with a water-resistant layer and creates short, bridge-like cross-links from fiber to fiber that maintain space between the strands and keep the leather pliable. In brain tanning, wood smoke is the tanning agent, creating natural aldehydes that—along with rigorous rubbing and stretching of the hide—create a soft suede. In vegetable tanning, naturally derived tannic acids play a similar role, yielding a variety of textures from tough leather for saddles and industrial belts to the soft fingers of a lady's kid glove.

"It's kind of fun, simple alchemy," Richards says with a smile.

Emulsified oil is rubbed into the skin, binding with the fibers to allow them to slide over each other and prevent the collagen from turning into glue. Brains are a classic source of emulsified oil—and an animal's brain provides just enough to tan its own hide, Richards notes. Eggs, cod oil, or olive oil can also do the job.

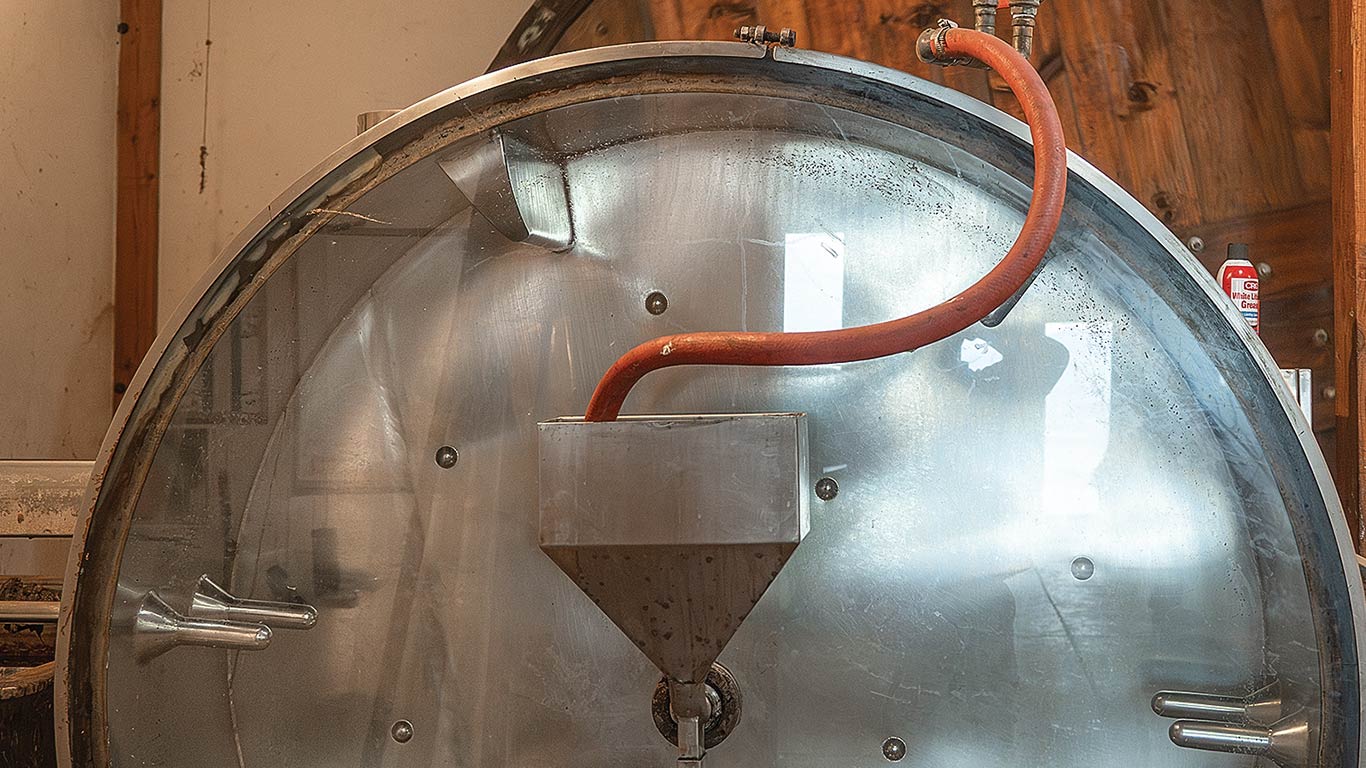

Above. Custom tanning hides for sheep and goat producers is a growing part of Traditional Tanners' business. Vintage machinery at Traditional Tanners has seen the rise and fall of the vegetable tanning industry. Hides soak in a century-old wooden drum. Tanning combines art and science. Michelle Richards stretches an oiled hide. Dylan Corey finishes a lush sheepskin at Traditional Tanners. Tanned hides from Axis deer, goats, sheep, and other animals are a wonderful canvas for Michelle Richards' imagination. This phone-size cross-body bag is one of Michelle's creations, as is the buckskin jacket behind it. Crafting leather clothes is among the most ancient arts.

Natural. Though they still do the occasional brain tan, Traditional Tanners is a vegetable tanning operation.

"Unlike brain tanning—which involves hours of softening each hide—you don't have to do anything to soften a bark-tanned hide beyond putting it in a big wooden drum," explains Matt.

"You can do that with one hide, 40 hides, or 4,000 hides and the labor investment is very small, versus with brain-tanning, you do all the softening by hand," he adds. "If you're really good at it, young, and willing to work your butt off, you can soften maybe four brain-tan hides a day. But bark tanning allowed hide processing to scale up to industrial levels."

Though 85 to 90% of the world's leather is tanned with chrome, Traditional Tanners have tapped a market for natural, bark-tanned products.

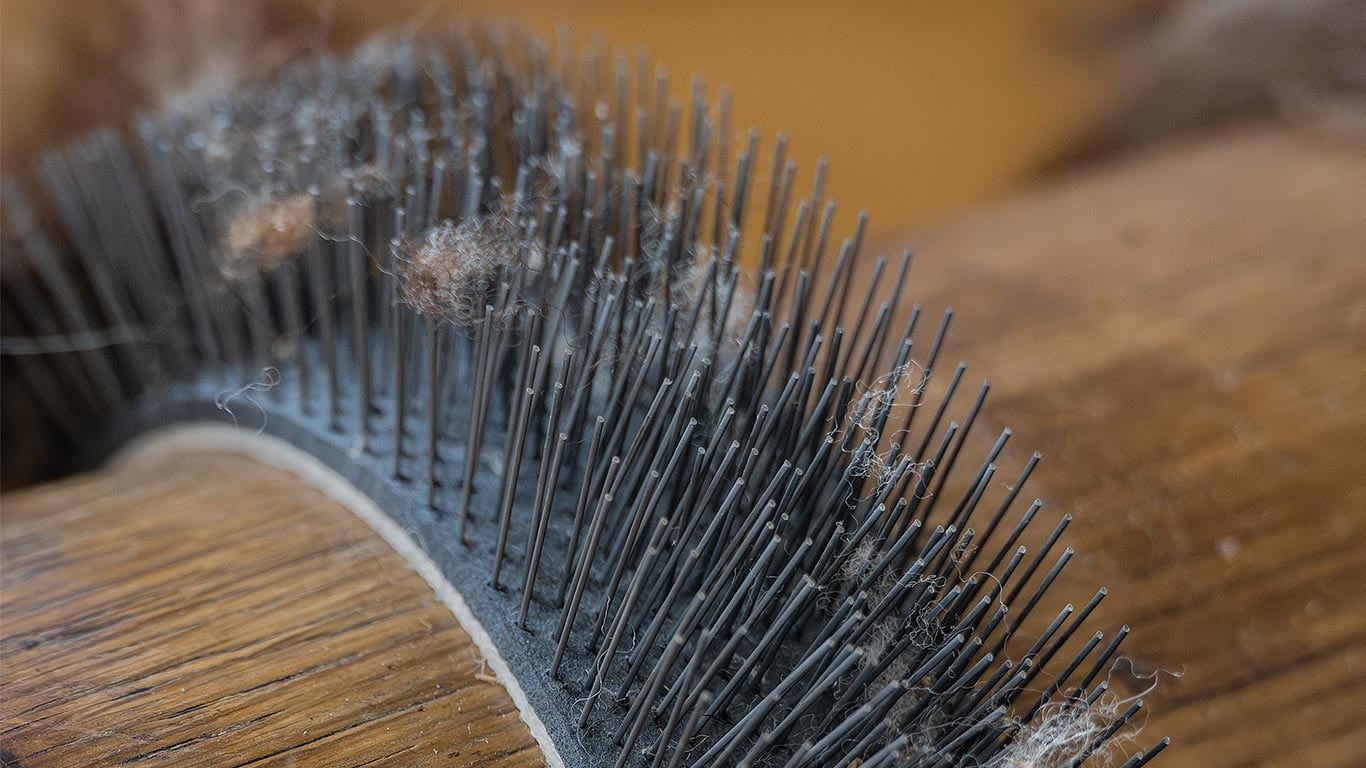

The company operates at a scale that once supported regional tanneries around the world, but now counts as an artisanal, craft-scale operation. Richards purchased most of the machines in the building—drums for alkaline baths, the paddle vats that agitate hides in the tannin tea, the spinner that extracts water after the rinse, the flesher that strips hides down to the skin, and the wooden tumbling drums that soften the hides—from small tanneries as they closed. The same goes for the belt sander that polishes the hides and the carding brush that combs the wool of freshly tanned sheepskin.

Matt and Michelle maintain supplies of sumac, which creates white leather suitable for dyeing, and mimosa, from the bark of an acacia tree, noted for fast tanning. Red oak, Western hemlock, and Turkish oak gall powder all have their strengths, too.

But the number-one tanning agent for Traditional Tanners is tanoak bark, which Matt harvests at logging sites on the California coast. Five years ago, he worked out a win-win arrangement with a logging company. Loggers must control tanoak populations so the fast-growing hardwood doesn't crowd out softwood seedlings. To Richards, tanoak bark is a rich source of natural tannin. His bark harvest kills the oaks, reducing the logging company's need to hire crews with chainsaws and herbicide to do the job.

Richards cures the bark in stacks for at least six months, grinds it in a chipper, and soaks it in tanks like 300-gallon batches of sun tea.

Great hides. Sourcing hides is a growing challenge. Most meat processors don't want to bother harvesting and salting hides, and if they do, they often cut the skins in ways that are not well-suited for leather making, Matt notes. Where Boy Scout troops commonly collected deer hides during hunting season to supply the deerskin glove industry, few still do. One of the best sources the Richardses have—a North Dakota bison processing plant where they buy hides harvested in the dead of winter, when the hair grows thickest—is a prized connection.

They have also fine-tuned a process to custom-tan hides for sheep producers. A fluffy, naturally tanned sheepskin can fetch hundreds of dollars. Fellow homesteaders and hunters can be good sources for hides for home-scale tanning, Matt points out.

Richards introduces people to brain tanning through his book and bark tanning through his Kitchen Table Tannery Zoom classes. He sends students kits with an untreated piece of hide and the other ingredients they need for tanning. The class meets weekly online throughout the process to go through steps together and compare notes on their progress. Through braintan.com, the Richardses sell not only their hides and leather, but also tanning supplies, guides, and sewing patterns. Interest in tanning at home is growing, note Matt and Michelle, especially among folks who like to know where their food and fabrics come from.

Scholar, teacher, and evangelist, Matt is eager to someday develop a tannery that could welcome visitors, just like an artisanal winery or artist's studio. After nearly 40 years spent mastering tanning, he still marvels at the age-old process and is eager to share it.

"It's really just magical that you can take this raw skin, put it in this tea, and it turns into leather and you're like, 'Wow—how did this happen?'" he says.‡

Read More

AGRICULTURE, SPECIALTY/NICHE

Scratching the Surface

Growing a market for all the weird stuff.