Agriculture, Farm Operation December 01, 2025

Boughs That Bind

Christmas tree farming connects land, family, and tradition.

Story and Photos by Katie Knapp

Fresh snow covers the rows at Krueger's Christmas Tree Farm in Lake Elmo, Minn., as families drag sleds and carry saws to an untouched section of the field.

The smell of balsam mixes with bonfire smoke from the warming house where hot cider waits. The scene keeps playing out as children giggle and parents dodge loose snowballs as if it were a holiday movie set.

"Make sure the tree has a price tag—that's how we track what we're selling," John Krueger calls to a family just starting out on their search.

What the families picking out their perfect tree might not realize is that the seven-foot fir being freshly cut, baled, and loaded onto their car represents nearly 15 years of planning and tending.

For a tree to be ready to harvest, it takes three years as a seedling, two years in transplant beds, and eight to ten years in the field with careful hand-trimming each and every summer.

Patient harvest. The Kruegers' story started when John's grandfather planted some spruce and pine trees along one of the farm's hillsides for erosion control. After neighbors asked to cut one for Christmas in the 1960s, they planted more and slowly transitioned from raising livestock to raising trees.

They now have a thriving, half pre-cut/half cut-your-own farm nestled inside the ever-expanding Minneapolis-St. Paul metro.

John says even though there is a steady stream of traffic past their farm every day, their customers don't see how much work goes into growing the perfect tree for them to enjoy.

"They don't see the weeks spent shearing in 90-degree summer heat, the drought years when whole fields die, or the gamble we take planting for a market that doesn't exist yet," he says.

Twelve hundred miles east in northern New Hampshire, Weir Tree Farms started similarly.

In June 1946, Jay Weir's grandfather bought 5,000 balsam fir transplants from the New Hampshire state nursery for $40. While neighbors continued cutting wild trees, he planted neat rows on his dairy farm.

"My grandfather was one of the first to cultivate Christmas trees," Jay says. "His peers told him he was crazy—there were wild trees everywhere. But he saw something different."

Those seedlings turned out to be exceptional, and he had the foresight to keep the best for seed production. Jay's father later grafted some of those original very blue, dense, late-budding trees onto others and created new hybrids, including their trademarked variety Fralsam™ Fir—a Fraser-Balsam cross.

Today, Jay still harvests seeds from the tall, grafted trees. He ships seeds as far as Europe and seedlings across the country from the nursery side of his business.

Above. Weir Tree Farms has grown Christmas trees from seed since 1946. Many of their seeds come from trees grafted from the original stock. Jay's son Jackson is the fourth generation to shear the trees by hand. Nigel Manley, of Bethlehem N.H., now uses an electric shearer on most of his trees but still prunes the leaders by hand.

Learning curve. "There's no school for Christmas tree farming, and you have to think generations ahead," Jay says. "You learn by doing, by watching, by making mistakes you won't see the results of for eight years."

That's where farmers like Nigel Manley come in. Originally from England, he came to New Hampshire after studying ag at the University of Minnesota through an exchange program.

"I was only going to grow trees for eight years. Nearly forty years later, I'm still growing them," he says with a laugh.

Nigel is now a director on the New Hampshire-Vermont Christmas Tree Association board, a state representative on the national association board, and a trustee for "Trees for Troops" (a non-profit organization that donates trees to U.S. military bases).

"Knowledge is so hard to transfer in this business," he explains, which is why he teaches workshops and uses his farm as a testing ground.

Currently he is experimenting with mulching methods to improve weed suppression and retain more moisture. He's also inter-planting new seedlings between mature trees. He believes the cooler soil temperature between established trees is helping the young trees grow better.

"More importantly," he adds, "it can generate income every four years instead of eight to ten."

Growing pains. After decades of manual pruning and lifting heavy trees at harvest, Nigel's shoulders demanded innovation.

"This saves my body while maintaining quality," he says while demonstrating his new electric shearer.

"Every field is different," he adds. "So what works on my small farm might not work for Jay's wholesale operation."

With significantly more trees than Nigel, labor challenges nearly ended Jay's operation a few years ago.

"I was going to have to cut my farm in half because I just didn't have any help," he says.

Thankfully, he could mechanize some tasks and hire through the federal H-2A Temporary Agricultural Workers program.

"I have hired the same three South Africans the past few years through the H-2A program. They arrive each April and stay through harvest and are great. With some new tools, a job that took six to eight men now takes two and a machine," Jay says happily.

Krueger, who also serves on the Minnesota association board, takes a different approach to solving labor challenges. He contracts traveling shearing crews and hires local high school students in the summer.

Land is also a big challenge for Kruegers. They recently placed 50 acres in a conservation easement to ensure their land will not be swallowed up by suburban development in the future.

"It's a voluntary restriction," John explains. "We still own the property and all the rights to it, but it limits future development. It will stay open space forever."

Above. Justin Goode pulls his sons, Lochlan and Torben, on a sled through Krueger's farm. Customers can either cut their own or choose a pre-cut tree at Krueger's Christmas Tree Farm in Minnesota, but for the last few years, everyone must first make a reservation online. Neil and John Krueger say this process has improved the overall experience—the atmosphere is still busy and energetic but without the chaos and long lines. Jay Weir checks the five-year-old Korean x Balsam Fir cross seedlings on his Colebrook, N.H., farm. The field next to Kruegers' warming house on a snowy December day showcases decades of hard work to produce warm holiday traditions and lasting memories that are movie-worthy

The December rush. John frames it like athletic training. "Summer is the hard work, trying to make sure everything grows and stays healthy. When December comes, it's like marathon day—you just run."

At his family's farm, roughly half choose pre-cut trees for convenience; the other half want "the adventure" of cutting their own.

"You get panic calls this time of year," John laughs. "You guys still open? You have trees?"

His dad Neil adds, "We stay open until Christmas Eve. We think it's more important to stay open and provide a tree for somebody that really wants one. We put a sign up and say 'help yourself to what's left.'"

Nigel agrees the small touches matter for the customers willing to pay a premium at a small farm.

He even had a local brewery make a "Trees for Troops" beer so he could help send more trees to military bases and give the families more reason to linger.

"Every little kid had a picture taken on the tractor and we were able to talk to everybody since they stayed for a while after their trees were loaded up." He adds, "Last year, several families sent me videos of their decorated trees, and many thank-you notes arrived weeks later."

Most of Weir's finished trees go to the wholesale market, so their rush really starts in October.

"We begin cutting in late October—after a few hard frosts—so trees can be on the lots by Thanksgiving," Weir explains.

"Contrary to what you might think, cutting them early isn't a bad thing," he says. "The timeline starts once it's in the house."

Making your tree last. No matter where you purchase a tree this season or what variety you choose, these farmers all say it's possible to keep it looking and smelling great in your living room well into the new year.

The key is consistent watering.

"Make a fresh cut, keep it cool and watered, and it'll last just as long as one cut yesterday," Jay advises. "If you let it go dry, even for half a day, it will seal over and stop drinking. That's when needles drop."

"I've had customers call in February saying their tree is still pliable and looking good," he adds. "As long as you keep water above that bark line, it'll last." ‡

Read More

AGRICULTURE, FARM OPERATION

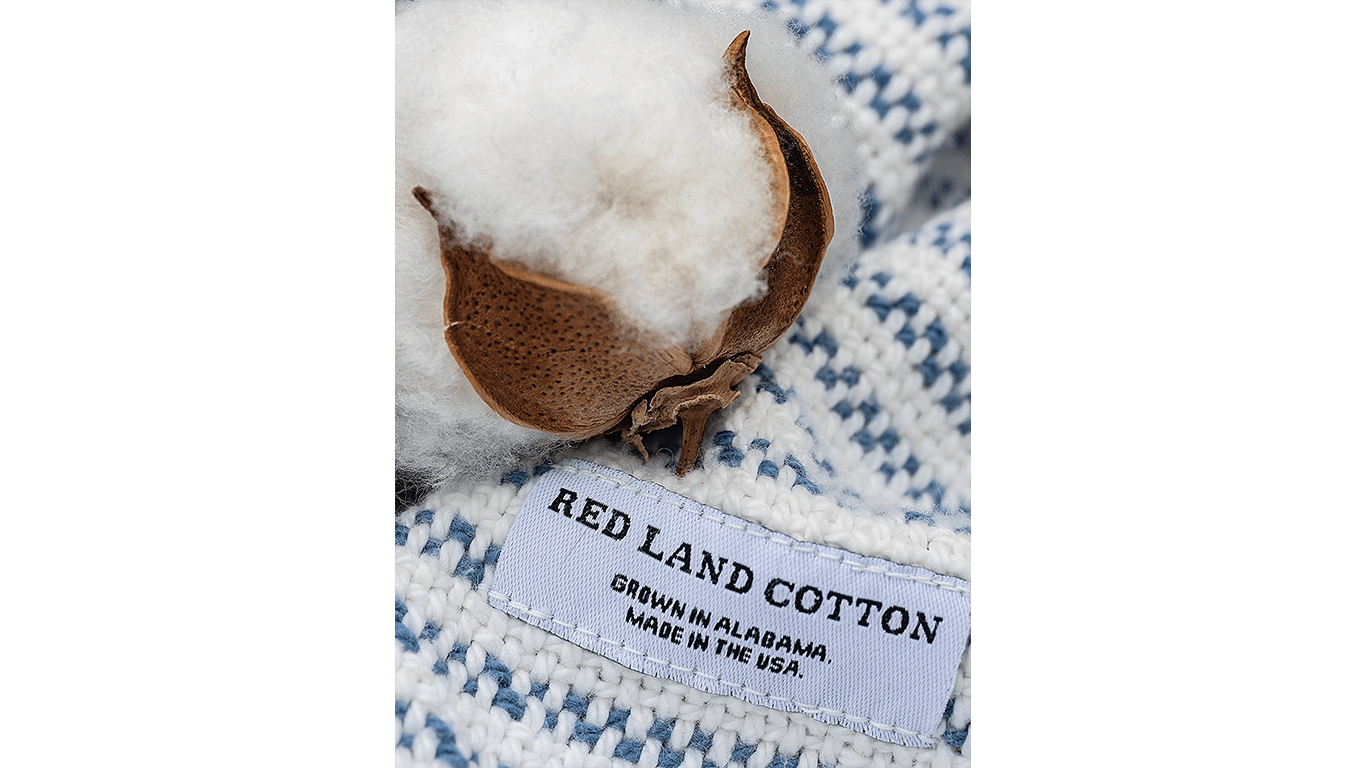

The Woven Path

Cotton farmers take fiber from field to function.

AGRICULTURE, SPECIALTY/NICHE

Scratching the Surface

Growing a market for all the weird stuff.